Executive Summary

The Fiscal Year 2025 HUD Continuum of Care (CoC) Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) and the high percentage of older adults living in Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) create an unprecedented crisis point.

HUD’s structural changes, specifically the new 30% Cap on Permanent Housing renewals, appear to assume a “recovery model” where tenants stabilize and move on to independent living. While this may work for some, our analysis of HUD’s Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) data indicates that at least 40% of current PSH residents are older people on fixed incomes.

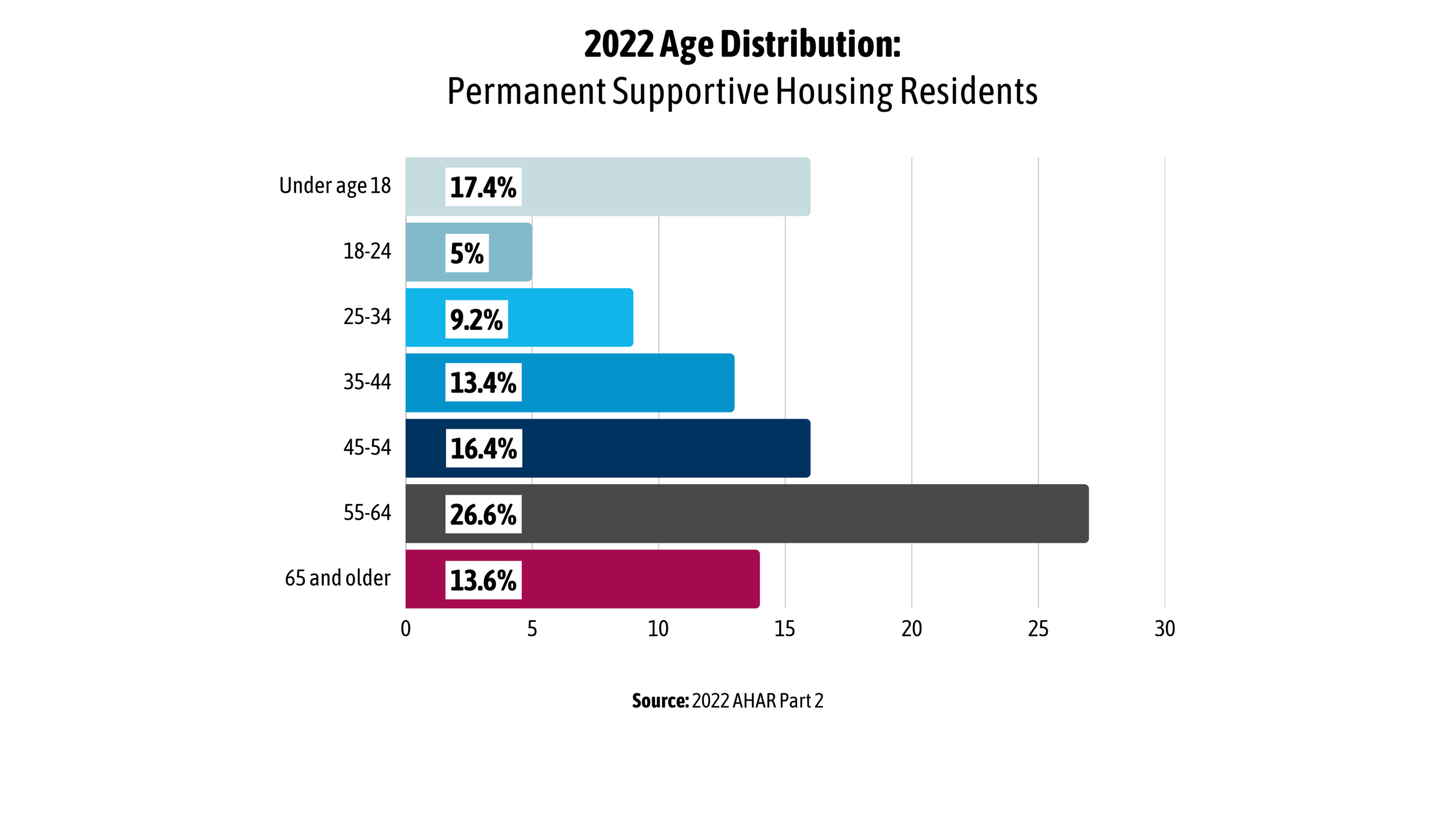

As of 2022, 40% of PSH residents were aged 55 or older1. Moreover, instead of creating healthy housing turnover, this one-size-fits-all policy will displace medically fragile adults into high-cost emergency systems (hospitals and nursing homes) or unsheltered homelessness.

HUD’s aging-related demographic trends indicate that the current policy direction may be fiscally and socially difficult to sustain. The changes do not account for aging or the health and income constraints common among older PSH residents. If renewal capacity is reduced without comparable alternatives, communities may see increased pressure on emergency and institutional systems, including hospitals, nursing homes, and unsheltered responses. Aligning funding mandates with the needs of older adults requires recognizing that, for many, success in PSH is defined by continued housing stability rather than eventual transition out.

These findings build on concerns we outlined in our recent press release,

A System Growing Older

According to HUD’s 2022 AHAR Part 2, residents in CoC-funded PSH are significantly older as a cohort than the general population. The PSH population is increasingly dominated by older adults. As of 2022, 40% of all PSH residents were aged 55 or older, more than double the rate found in the total population experiencing sheltered homelessness1. Based on HUD’s data, approximately 68,000 residents over 55 are estimated to be currently living in CoC-funded permanent supportive housing.

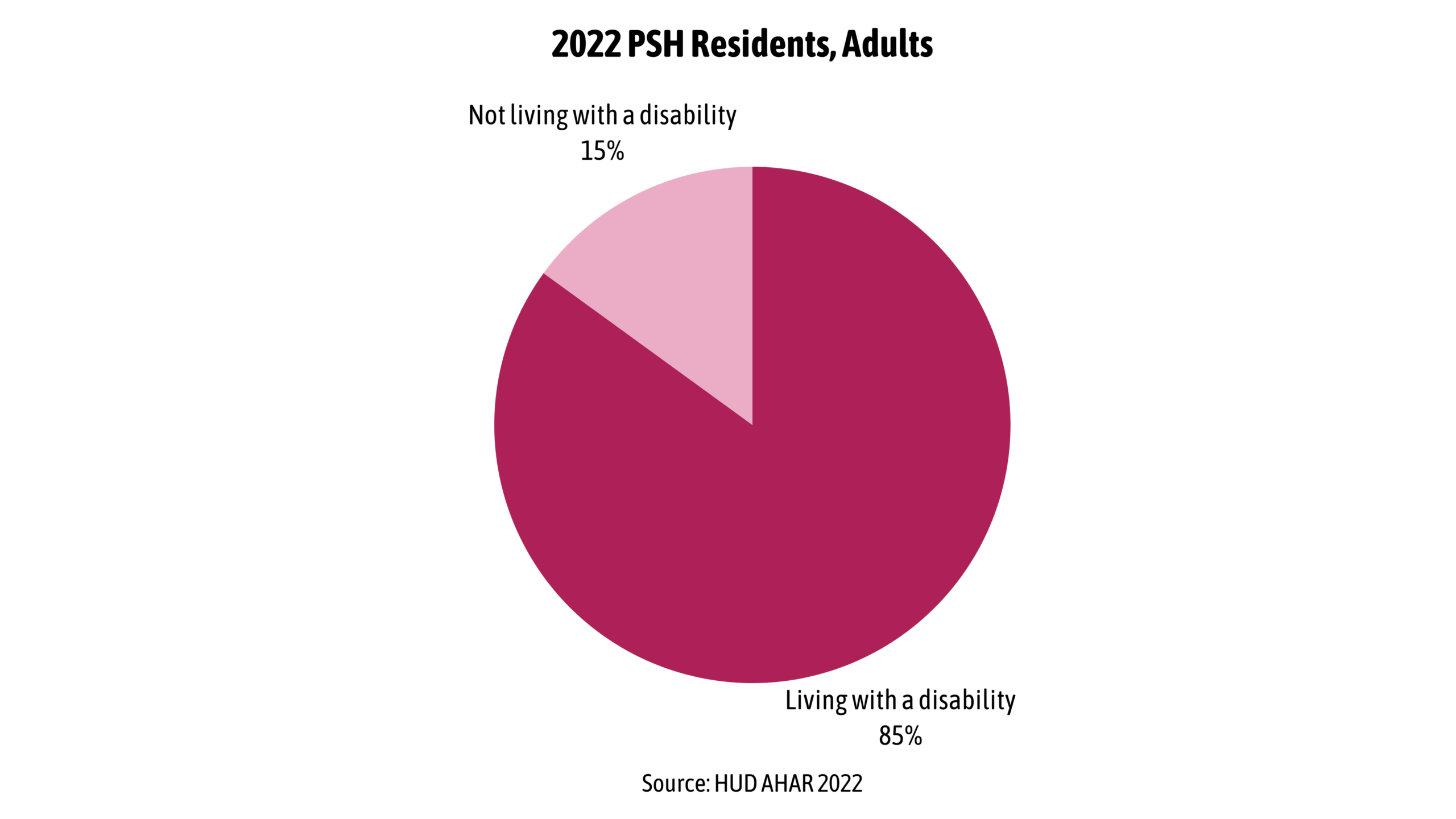

This trend is accelerating, evidenced by a 62% increase in residents aged 65 and older between 2019 and 2022, while the population of residents under 35 declined by 12%1. This shift indicates that older adults are retaining units for longer durations. Regardless of age, according to HUD’s AHAR, as of 2022, 85.3% of adult residents of PSH were living with a disability.

Standard definitions of “elderly” underestimate the health status of this population. Research published in The Gerontologist confirms the phenomenon of “accelerated aging,” finding that homeless adults exhibit geriatric conditions at rates comparable to housed individuals who are approximately 20 years their senior3. A typical 50-year-old PSH resident often presents the medical profile of a 70-year-old, with nearly half reporting difficulty with at least one Activity of Daily Living (ADL) such as bathing or dressing4.

FY 2025 NOFO Mechanisms

The FY 2025 NOFO introduces structural changes that presume the existence of a housing market capable of absorbing tenants who “move on.” For the aging PSH cohort, this presumption is fundamentally in conflict with the housing market and demographic realities.

The 30% Cap vs. “Aging in Place”

The NOFO mandates that no more than 30% of a CoC’s Annual Renewal Demand (ARD) may be used for Permanent Housing. This creates an immediate conflict for older adults in PSH. These tenants are unable to “move on” to market-rate housing because their fixed income cannot support it, and they are not able to afford existing Assisted Living models that rely on the ability of residents to pay monthly fees averaging $5,3502.

Since these tenants cannot voluntarily exit to private pay assisted living options, complying with the 30% cap will require CoCs to defund occupied units. This effectively mandates the eviction of long-term, older tenants to satisfy an arbitrary portfolio ratio.

Reducing Tier 1 protection to 30% of ARD undermines the stability required for fixed-income planning, as older adults rely on the certainty of rental assistance and services to maintain health stability. The impact of capping Tier 1 protections on residents in PSH can be expected to exacerbate their physical and mental health challenges and increase their utilization of high-cost hospital-based care.

Economic and Health Impact Analysis

The displacement of older adults from PSH signifies a massive increase and cost shift to healthcare and state budgets.

Displacing older adults with complex care needs from PSH does not save money but shifts costs to significantly more expensive budget lines. While PSH costs approximately $16,000 per year for housing and services5, a year in a Medicaid Skilled Nursing Facility exceeds $100,0002. Furthermore, a single hospitalization for a fall or unmanaged condition can easily surpass the entire annual cost of a resident’s supportive housing. By increasing the likelihood of institutionalization and acute care usage, these policy changes will reverse established savings and generate a net negative fiscal impact.

There is an insurmountable financial gap preventing independent PSH residents from moving to more supportive environments (such as Assisted Living). With an average monthly income of $914 (SSI rate) against a $5,350 average monthly cost of Assisted Living care2, PSH is the only viable housing option between unsheltered homelessness and a Skilled Nursing Facility. Defunding PSH removes the lowest, most effective/efficient rung of the long-term care ladder, creating a dangerous and costly gap that will fall on healthcare systems and state governments.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The FY 2025 NOFO fundamentally restructures the CoC program’s financial architecture. By capping Permanent Housing renewals at 30% and significantly reducing Tier 1 protections, the policy forces a contraction of the subsidized rental market, with vulnerable seniors being severely impacted. In the case of displaced aging adults, this approach fails to achieve federal savings and increases costs to healthcare systems and states due to inevitable stays in hospitals, long-term care, and other institutions.

We recommend the following actions

- Immediate Congressional action to preserve homes and prevent negative economic and community impacts:

- Congress should direct HUD to renew all CoC grants expiring in calendar year 2026 for a full 12 months to preserve the homes of tens of thousands of older adults and provide time to mitigate harmful policies.

- Local flexibility and pragmatic tools.

- Federal policy should give communities the flexibility to preserve the housing needed to support people struggling with rising housing costs and chronic health conditions to prevent and reduce homelessness and provide cost-effective care.

Footnotes and Research

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2023). The 2022 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, Part 2: Estimates of Homelessness in the United States. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/AHAR-Part-2-2022.pdf

- Genworth Financial. (2023). Cost of Care Survey 2023. https://www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.html

- Brown, R. T., Hemati, K., Riley, E. D., Lee, C. T., Ponath, C., Tieu, L., Coe, M., & Kushel, M. B. (2017). Geriatric conditions in a population-based sample of older homeless adults. The Gerontologist, 57(4), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw011

- UCSF Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative. (2023). Toward Dignity: Understanding Older Adult Homelessness. University of California, San Francisco. https://homelessness.ucsf.edu/resources/reports/toward-dignity-understanding-older-adult-homelessness

- Jacob V, Chattopadhyay SK, Attipoe-Dorcoo S, Peng Y, Hahn RA, Finnie R, Cobb J, Cuellar AE, Emmons KM, Remington PL. Permanent Supportive Housing With Housing First: Findings From a Community Guide Systematic Economic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2022 Mar;62(3):e188-e201. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.08.009. Epub 2021 Nov 10. PMID: 34774389; PMCID: PMC8863642.

Further Reading

This assessment is part of a broader look at how the NOFO may affect the people and systems that keep communities housed.

Read our companion analysis: