Key Takeaways

- The FY 2025 CoC Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) forces a large-scale shift away from Permanent Housing. By capping Permanent Housing (PH) renewals at 30 percent of Annual Renewal Demand (ARD) and reducing Tier 1 protection to 30 percent, HUD makes most PH renewals both noncompliant and fully competitive, requiring widespread conversion or elimination of PH projects regardless of performance.

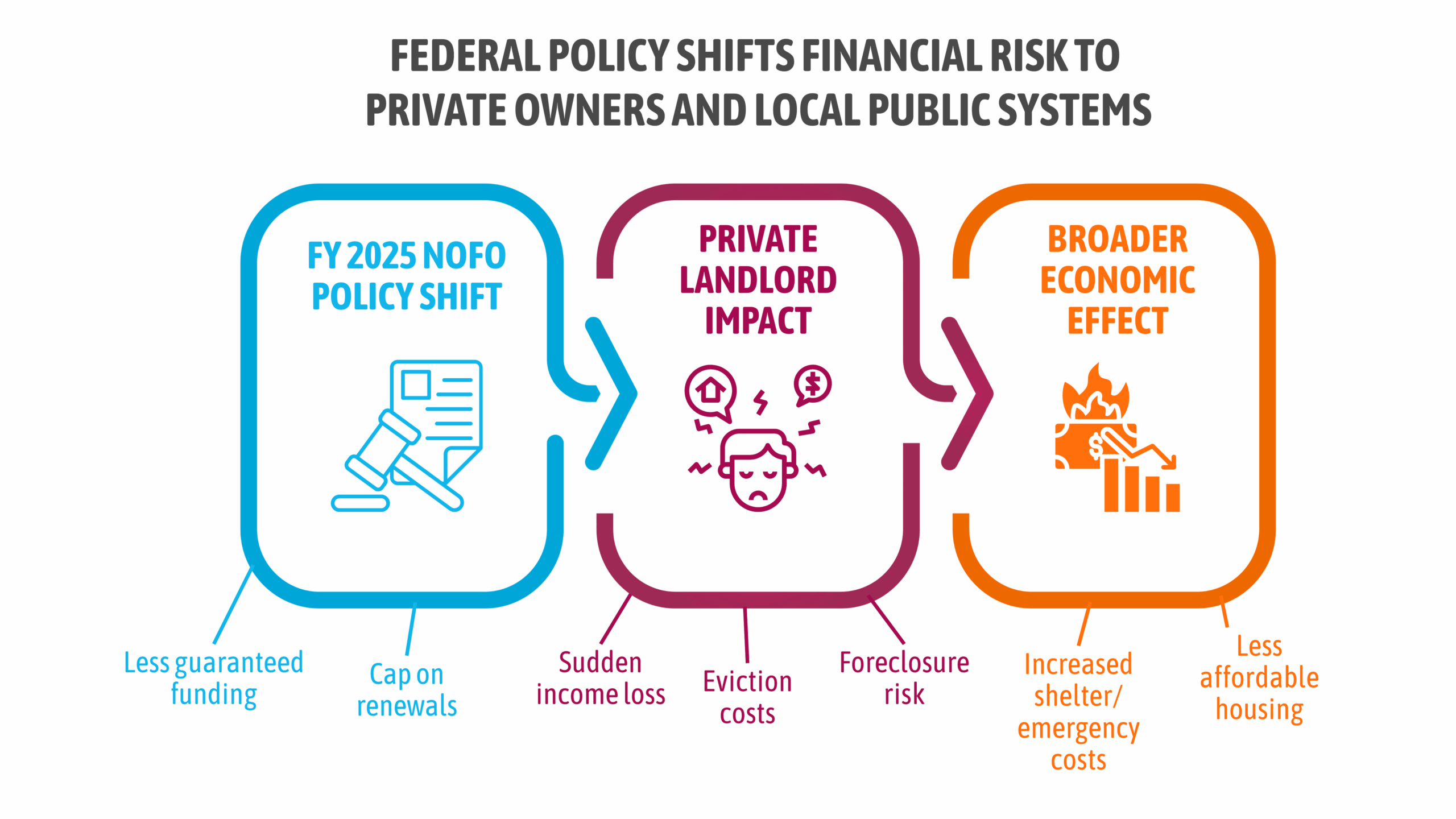

- Private landlords, especially in Class B and C stock, face a major and nationwide revenue shock. Tenant-based CoC rental subsidies underpin thousands of private leases; the new structure puts roughly $1.8B in annual rental payments at risk, potentially affecting over 100,000 PH homes across 700-plus communities in nearly every state.

- The changes increase eviction and system pressure unless Congress or HUD intervenes. Abrupt tenant-based rental assistance losses make lease non-renewal and non-payment terminations more likely, raising displacement risk for current tenants and shifting downstream costs to shelters and local crisis systems, which supports the need for immediate federal action and restored local flexibility.

Executive Summary

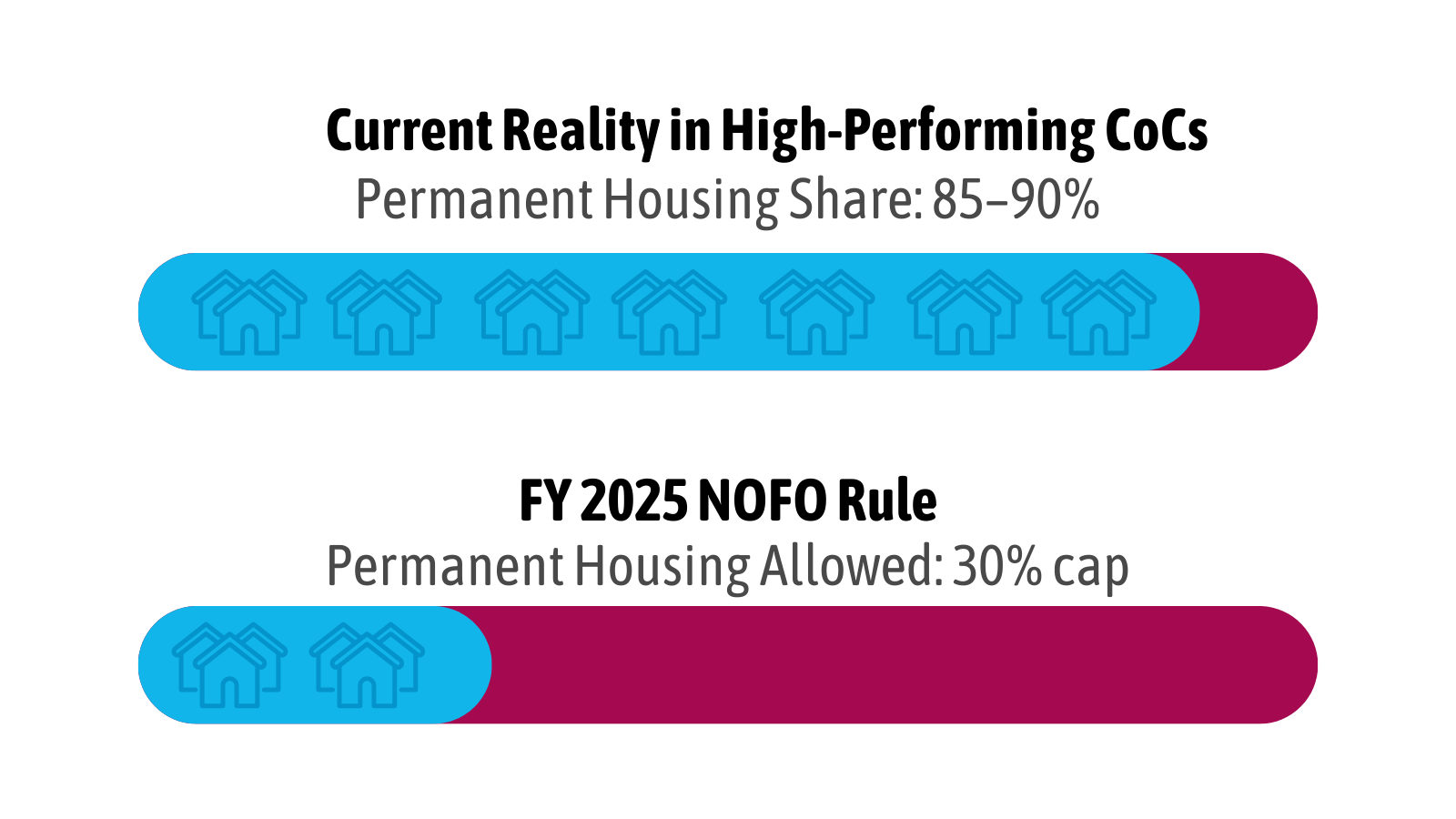

HUD has released the FY 2025 CoC NOFO, making structural changes that substantially constrain Permanent Housing as a local strategy. The NOFO limits Permanent Housing renewals to 30 percent of each CoC’s Annual Renewal Demand1 (including PSH2, RRH3, and Joint TH-RRH4) and reduces Tier 1 renewal protection to 30 percent of ARD, down from about 90 percent in recent years. As a result, CoCs must convert or eliminate Permanent Housing projects above the cap and submit most remaining renewals in Tier 2, where they face full competition.

This report examines these structural changes and estimates their effects on local private rental markets. Private landlords are likely to face significant downstream impacts. CoC Tenant-Based Rental Assistance (TBRA), paired with CoC-funded supportive services, has historically linked tenants to private market units, providing steady rental revenue for landlords in mid and lower cost multifamily stock, especially Class B and Class C properties.

Our analysis finds that the 30 percent Permanent Housing cap, coupled with the Tier 1 reduction, materially threatens the stability of existing private market leases. Based on current CoC Permanent Housing spending patterns, ARD levels, and average rents, we estimate that a large portion of the roughly $1.8 billion in annual rental payments to private landlords is at risk. This exposure could affect more than 100,000 of the approximately 170,000 CoC-funded PSH homes across 700-plus communities nationwide. Full assumptions and calculations are in Appendix A.

If these subsidies are reduced or converted at scale, the policy shift is projected to raise the likelihood of lease non-renewals, involuntary moves, and eviction risk for thousands of current leaseholders, while transferring significant fiscal pressure to local emergency shelter systems and other crisis-response budgets.

These findings build on concerns we outlined in our recent press release, which calls for urgent congressional action to prevent further destabilization of local housing markets.

FY 2025 CoC NOFO Changes

To accurately assess the market impact, stakeholders must understand how the FY 2025 NOFO redefines the funding architecture that underpins local housing contracts.

The Recalibration of Tier 1 and Tier 2 Funding

HUD requires CoCs to rank projects into two funding tiers. Historically, Tier 1 protected about 90 to 95 percent of a community’s Annual Renewal Demand, allowing landlords to treat CoC grants as secure, government-backed revenue suitable for long-term leases. Tier 2 covered the remaining competitive share, where renewals are scored nationally and therefore cannot reliably support multi-year rental contracts. The FY 2025 NOFO reverses this structure by limiting Tier 1 to 30 percent of ARD, pushing roughly 70 percent of existing housing contracts into Tier 2 and turning what stable renewals were into high volatility funding.

The 30% Cap on Permanent Housing

Beyond tiering, the NOFO imposes a rigid cap on Permanent Housing renewals. Permanent Housing refers to long-term rental assistance that renews annually, primarily serving formerly homeless households with disabilities and very low or fixed incomes. Under the new rule, no more than 30 percent of a CoC’s ARD may be committed to PH projects, including PSH, RRH, and Joint TH-RRH. Because most CoCs currently devote roughly 85 to 90 percent of their portfolios to housing-focused programs with strong performance records, the cap creates a mathematical compliance problem. To meet it, communities may have to eliminate or convert large numbers of Permanent Housing contracts regardless of local need or results.

Real Estate Asset Class Exposure

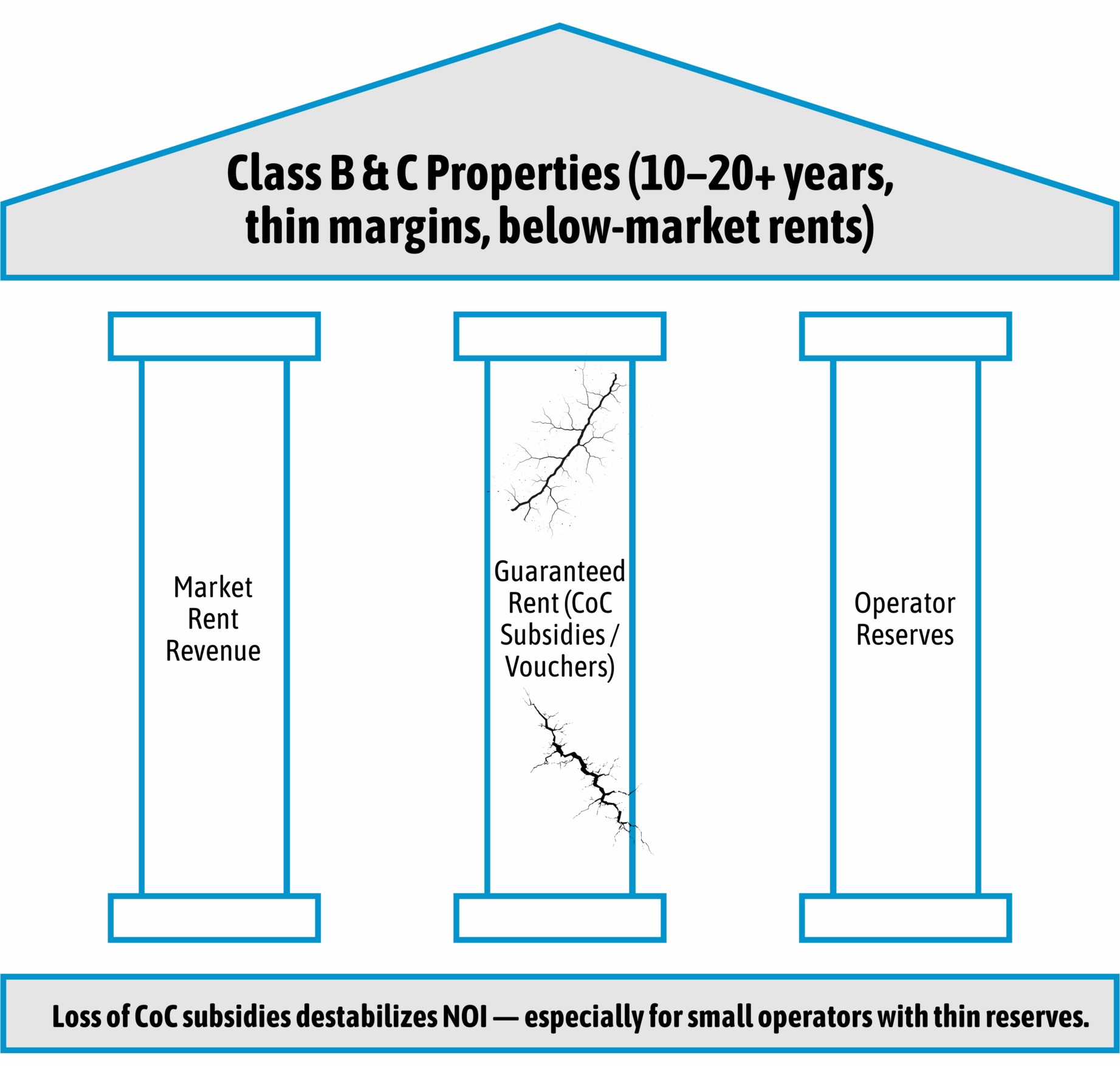

The economic impact of these policy shifts is not distributed evenly across the real estate market but is concentrated within specific asset classes that serve as the backbone of the voucher ecosystem.

The primary exposure lies within Class B and Class C properties. Class B assets are generally older (10–20 years) but well-maintained properties that command average market rents, often housing middle-income tenants alongside voucher holders. Class C assets represent older stock (20+ years) with potential deferred maintenance and below-market rents. These properties anchor many neighborhoods yet often operate on thin profit margins where guaranteed government rent payments serve as the primary stabilizer of income. The withdrawal of CoC subsidies & services support threatens to disrupt the financial equilibrium of these properties, particularly for smaller operators who lack the capital reserves to weather sudden revenue stops.

Mechanisms of Market Disruption

The FY 2025 NOFO introduces structural risks that threaten to dismantle the financial security previously inherent in the housing-focused model.

Complying with the 30 percent Permanent Housing cap will force many CoCs to shrink their PH portfolios, directly jeopardizing private market leases. Tenant-Based Rental Assistance is tied to individual landlord-tenant leases, not to a building, and often allows households to live near work, services, and family supports. If a PH grant is terminated to meet the cap, the subsidy can end abruptly. The lease may remain in place, but most tenants cannot cover full market rent, shifting immediate loss risk to landlords and making non-payment terminations more likely.

Reducing Tier 1 to 30 percent effectively shifts most renewals into Tier 2. For landlords, that change raises the perceived risk of participating in CoC-funded leasing. Many owners are likely to respond by limiting participation or exiting altogether, since higher rents are largely constrained by Fair Market Rent limits. Over time, this volatility could shrink the supply of private market units available to voucher holders.

Financial Impact on Private Landlords

The policy changes present a revenue cliff for property owners, with small-scale investors (“mom and pop” landlords) facing the most severe exposure.

Income Reduction and Mortgage Default Risk

For a standard unit renting at $1,500, the CoC subsidy typically covers around $1,200. The termination of this subsidy results in an immediate 80% revenue reduction for that unit. For properties with a high concentration of voucher holders, this aggregate loss can drive Net Operating Income below the Debt Service Coverage Ratio, triggering mortgage default. This financial stress is compounded by the operational costs of eviction. Landlords forced to reclaim units face legal and administrative fees averaging $3,500 to $10,000 per unit. Due to court backlogs across the country, vacancy losses can persist for 6 to 12 months, during which the owner remains liable for taxes, insurance, and maintenance costs without offsetting revenue.

State-Level Economic Exposure

Using 2024 Housing Inventory Count data mapped to 2026 Fair Market Rents, we estimate annualized tenant-based CoC spending at risk across nearly every state and more than 700 communities nationwide. While exposure is heaviest in some high-cost states, such as California ($344M), the risk is broadly distributed and substantial in other states as well, including Florida ($66M), Texas ($49M), and Missouri ($46M). These figures are likely conservative given CoC funding increases over the past year.

Conclusion and Strategic Impact

The FY 2025 NOFO represents a fundamental restructuring of the CoC program’s financial architecture. By capping Permanent Housing renewals at 30% and significantly reducing Tier 1 protections, the policy effectively mandates a contraction of the affordable rental market. This approach achieves federal savings primarily by transferring financial risk to private property owners and operational costs to state and local-level emergency systems.

We are recommending the following actions:

- Immediate Congressional action to preserve homes and prevent negative economic and community impacts: Congress should direct HUD to renew all CoC grants expiring in calendar year 2026 for a full 12 months to preserve the homes of tens of thousands of Americans and provide time to mitigate harm.

- Local flexibility and pragmatic tools. Federal policy should allow communities the freedom to invest in preserving critical existing housing, protect the landlords who make these homes available, support those struggling to keep up with rising housing costs, and prevent increased homelessness.

References

- Decker, N. (2021). The Uneven Impact of the Pandemic on the Tenants and Owners of Small Rental Properties. Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2025). FY2025 CoC Program NOFO Full Analysis.

- National Association of Counties. (2025). HUD’s Continuum of Care Faces Program Changes and Funding Uncertainty.

- The Eviction Lab. (2024). Eviction Tracking System.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2024). 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) Part 1.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2024). CoC Program Leasing and Rental Assistance Requirements.

Appendix A: Methodology

This assessment applies a quantitative approach to estimate the revenue at risk for private landlords under the FY 2025 CoC NOFO over a 12-month period. The model isolates tenant-based PSH beds and excludes non-profit-owned, master-leased, or facility-based inventory to avoid double-counting and to focus on private sector lease exposure.

Data Architecture

The core dataset is HUD’s 2024 Raw Housing Inventory Count, representing the national census of active CoC-funded PSH projects in that year. Projects were geocoded to HUD administrative geographies and counties, then matched to 2026 one-bedroom Fair Market Rents. Annualized assistance value was computed as FMR multiplied by 12 months for each tenant-based unit, producing a jurisdiction-level estimate of TBRA rental flow.

After FMR matching, projects coded as tenant-based were isolated to estimate private market exposure. Tenant-based differs from project-based assistance because subsidy payments follow the household into privately owned units rather than flowing to a fixed site or master lease holder. Restricting the sample to TBRA, therefore, yields a targeted estimate of rental revenue at risk within the private multifamily sector.

Within the tenant-based sample, we identified projects receiving any CoC grant support, including either tenant-based rental assistance or CoC-funded supportive services. Because supportive services are integral to the PSH model and to lease stability, we treat all tenant-based PSH projects with CoC funding as carrying comparable landlord exposure, regardless of whether the CoC contribution is recorded as rental assistance or services.

Annualized revenue at risk equals monthly FMR imputed rent multiplied by 12 for each TBRA unit, aggregated to the state and national level. The model treats current PH TBRA projects as exposed to discontinuation under two regulatory mechanisms: (1) portfolio displacement required to comply with the 30 percent Permanent Housing renewal cap, and (2) renewal volatility created by limiting Tier 1 protection to 30 percent of ARD, which shifts most PH renewals into Tier 2 competition

Limitations

This analysis provides an exposure estimate, not a prediction of realized losses. Because HUD does not publish unit counts for most tenant-based inventory (except family units, which represent about 12 percent of tenant-based stock), we assume beds are a reasonable proxy for units. The model further assumes that FY 2024 tenant-based Permanent Housing beds are broadly exposed to displacement under the FY 2025 cap and tiering rules, though realized outcomes will depend on local reallocation choices, HUD scoring results, and any future Congressional or administrative action. Fair Market Rents are used as an imputed rent proxy and may differ from contracted CoC lease rates in some jurisdictions. The model also does not capture secondary effects such as landlord behavioral responses, spillover into other voucher programs, or time lags between grant decisions and lease terminations. Estimates should therefore be interpreted as a conservative upper bound on private-market rental revenue at risk.

Appendix B: Estimated Annualized Payments to Private Landlords by State

| State | Annualized Payments | State | Annualized Payments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska – AK | $1,533,768 | Montana – MT | $907,452 |

| Alabama – AL | $11,748,336 | North Carolina – NC | $33,753,045 |

| Arkansas – AR | $700,884 | North Dakota – ND | $835,680 |

| Arizona – AZ | $59,502,432 | Nebraska – NE | $2,342,844 |

| California – CA | $343,728,084 | New Hampshire – NH | $2,940,624 |

| Colorado – CO | $28,949,040 | New Jersey – NJ | $46,287,264 |

| Connecticut – CT | $59,067,560 | New Mexico – NM | $6,661,080 |

| Washington, D.C. | $24,494,340 | Nevada – NV | $11,650,032 |

| Delaware – DE | $6,013,620 | New York – NY | $138,928,224 |

| Florida – FL | $65,923,332 | Ohio – OH | $142,756,608 |

| Georgia – GA | $39,424,092 | Oklahoma – OK | $3,567,583 |

| Guam – GU | $1,177,092 | Oregon – OR | $37,378,679 |

| Hawaii – HI | $4,417,812 | Pennsylvania – PA | $90,639,192 |

| Iowa – IA | $4,150,488 | Puerto Rico – PR | $6,999,492 |

| Idaho – ID | $3,355,712 | Rhode Island – RI | $7,400,424 |

| Illinois – IL | $84,080,448 | South Carolina – SC | $7,800,432 |

| Indiana – IN | $9,992,340 | South Dakota – SD | $508,776 |

| Kansas – KS | $7,631,832 | Tennessee – TN | $16,438,358 |

| Kentucky – KY | $20,100,276 | Texas – TX | $49,036,186 |

| Louisiana – LA | $29,734,452 | Utah – UT | $17,563,608 |

| Massachusetts – MA | $98,614,248 | Virginia – VA | $21,475,740 |

| Maryland – MD | $62,135,028 | Vermont – VT | $1,830,072 |

| Maine – ME | $24,566,868 | Washington – WA | $50,944,104 |

| Michigan – MI | $62,137,440 | Wisconsin – WI | $17,057,030 |

| Minnesota – MN | $17,935,288 | West Virginia – WV | $4,585,584 |

| Missouri – MO | $45,806,776 | Wyoming – WY | |

| Mississippi – MS | $202,728 | ||

| TOTAL | $1,837,412,430 |

Note: These figures represent approximate annualized impacts based on HUD data. They are specific to tenant-based assistance and exclude other project types (e.g., project-based or site-based units).

Footnotes

- Annual Renewal Demand (ARD) is the total dollar amount a Continuum of Care needs to renew all existing CoC-funded projects eligible for renewal in that competition year. HUD calculates ARD from the CoC’s Grant Inventory Worksheet and uses it as the baseline for setting local funding limits and tiers. ↩︎

- Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH): A CoC permanent housing component that provides long-term housing assistance, such as leasing or rental assistance, paired with ongoing supportive services for households with at least one member with a disability, to support housing stability. ↩︎

- Rapid Rehousing (RRH): A CoC permanent housing component that offers short-term or medium-term tenant-based rental assistance, generally up to 24 months, plus housing-focused services to help people experiencing homelessness move quickly into permanent housing and stabilize there. ↩︎

- Joint TH-RRH (Joint Transitional Housing and Rapid Rehousing): A single CoC project component that combines Transitional Housing activities with RRH rental assistance, allowing participants to begin in time-limited transitional housing and then transition directly into RRH within the same project as they become ready for permanent housing. ↩︎

Further Reading

This assessment is part of a broader look at how the NOFO may affect the people and systems that keep communities housed.

Read our companion analysis: