This learning brief synthesizes evidence regarding inflow from incarceration into homelessness and outlines the unique housing challenges people experience after incarceration. It also highlights promising practices and findings from evaluations of initiative programs that help formerly incarcerated individuals access and secure safe and affordable housing. This page contains a summary.

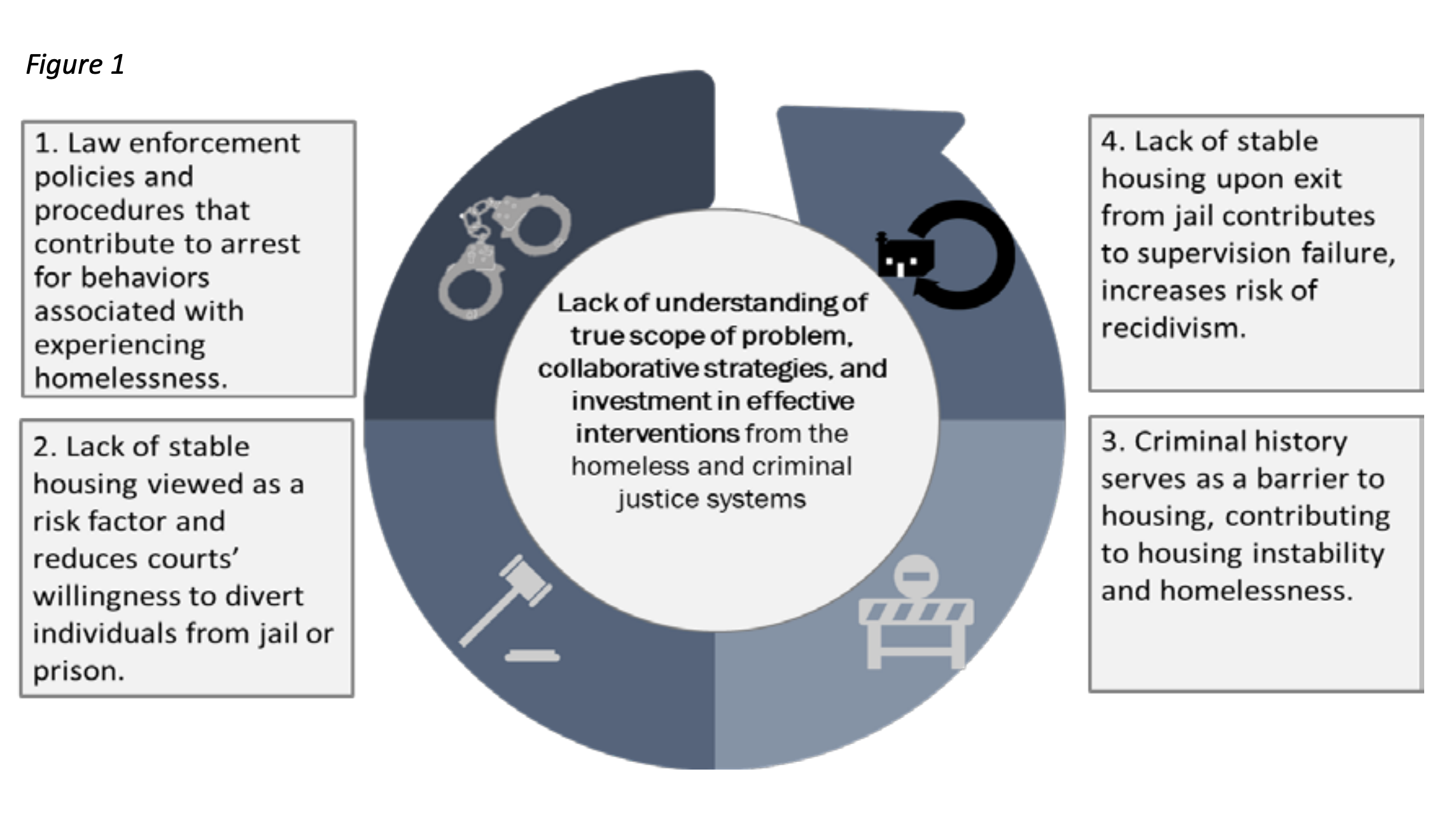

Homelessness and criminal legal system involvement are deeply intertwined, and each experience is a risk factor for the other.1 Due to systemic and structural barriers in the housing, criminal legal, and other systems, people of color — especially Black people — are drastically overrepresented in the currently and formerly incarcerated population, as well as those experiencing homelessness in the U.S.

Mass incarceration has necessarily generated mass reentry. Well over 600,000 individuals in the U.S. make the transition from state or federal prison to community living each year. An additional 9 million exit local jails annually.2 These individuals are significantly more likely than the general public to have already experienced homelessness and experience homelessness after release. This results in a revolving door through which people — largely people of color — cycle between incarceration and homelessness.

Stable housing is a crucial foundation for formerly incarcerated individuals to be able to reunite with their families, access and receive necessary health care and treatment, and secure employment — factors that promote successful reentry and reduce recidivism risk.3

Yet, formerly incarcerated people make up between 23.1-47.8% of annual homeless shelter admissions, and are 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general population.4

Figure 1: The Cyclical Relationship between Housing Instability and Criminal Legal System Involvement5

This brief synthesizes the evidence regarding inflow from incarceration into homelessness and the unique housing challenges people experience after incarceration. We also highlight promising practices and describe findings from evaluations of innovative programs that assist formerly incarcerated individuals in accessing and securing safe and affordable housing.

Risks of homelessness after incarceration

We find that regulatory restrictions often impose temporary bans or permanent exclusion of people with criminal records from public housing, and local practices add to these restrictions, resulting in challenges for family reunification and barriers to affordable housing. These barriers, in combination with unequal treatment in the private rental market, contribute to stark rates of homelessness for this population.

Our review found that there is variability in homelessness risk and experience across incarceration history, gender, and race. For example:

- People who have beenincarcerated more than once are 13x more likely to be homeless than the general public.

- People who have been out of prison for two years or less are over twice as likely to be homeless as those who have been living in the community for four years or longer.

- Formerly incarcerated women are more likely to be homeless than formerly incarcerated men (i.e., 264 per 10,000 women vs. 195 per 10,000 men)

- Among formerly incarcerated people experiencing homelessness, men are less likely to be sheltered than women (i.e., 90 per 10,000 men vs. 156 per 10,000 women)

- Formerly incarcerated Black men experience unsheltered homelessness at a rate greater than formerly incarcerated Hispanic or White men (124 per 10,000 Black men vs. 82 per 10,000 Hispanic men & 81 per 10,000 White men)

- Formerly incarcerated Black women experience sheltered homelessness at a rate 4x that of White men and 2x that of Black men (203 vs. 56 and 108 per 10,000, respectively)

- Incarceration during adolescence or from age 18-23 predicts a younger age of initial homelessness (i.e., 9.8 years or 5.1 years earlier, respectively)6

Barriers to Public Housing

A number of legal and regulatory barriers restrict formerly incarcerated people from accessing public housing and federally-assisted housing, though many of these restrictions apply to individuals with a wider range of criminal legal system involvement.

- The Cranston-Gonzalez National Affordable Housing Act of 1990 places a mandatory 3-year ban on the readmission of tenants evicted for drug-related criminal activity.

- 42 U.S. Code §13663 permanently excludes people with convictions that require lifetime sex offender registration in any state from any public housing

- 42 U.S. Code §1437n permanently excludes people who have been convicted of methamphetamine production on the premises of any type of federal government-assisted housing

- 23 state-level statutory and regulatory codes restrict access to public housing for people with criminal records7

Congress also grants public housing authorities and federally-assisted housing owners the authority to deny admission to applicants with criminal histories. Though Congress specifies this authority holds if the applicant (or any member of their family) had engaged in criminal activity within a “reasonable time” preceding application, there is no guidance regarding what length of time qualifies as reasonable. This results in denials based on overly long lookback periods in criminal record screenings. In addition, as the federal definitions of chronic and general homelessness exclude people who have been incarcerated for over 90 days, formerly incarcerated people are often ineligible or not prioritized for public housing assistance.

With broad discretion, public housing authorities and project owners often supplement federal policies with additional screening criteria and eviction policies. Criminal background lookback periods are often 7-10 years, and some stretch as far back as 20 years.8 Thus, many formerly incarcerated people must wait seven years or longer after their convictions before becoming eligible for public housing. Although housing providers differ in terms of which events trigger denial (i.e., arrest, conviction type), these often include relatively minor offenses and/or mere arrests.

Because formerly incarcerated people frequently intend to live with their families upon release,9 if their family members live in public housing, formerly incarcerated people are faced with the hard choice between undesirable options: ask their families to move (which is often infeasible), move in with their family and put them at risk of eviction, seek alternative housing (i.e., halfway house, shelter), or live on the street.

Barriers to Private Housing

Considering the high rates of joblessness (over 60%) and limited financial means among formerly incarcerated people,10 many are unable to afford renting in the private housing market. Even for those who have the means, however, landlord stigma, as well as crime-free ordinances or nuisance laws, can reduce private housing opportunities. Research illustrates significant stigma and unequal treatment among landlords against people with criminal histories, and landlords often report excluding formerly incarcerated people due to anticipated concern and fear from other renters.11

Crime-free rental housing ordinances, also called nuisance laws, pressure landlords to control crime on property in around 2,000 cities across the U.S.12 These ordinances often require landlords to complete crime-free training, have tenants sign a crime-free lease addendum, and run background checks as a condition of landlord licensure. These trainings — sometimes conducted by city police departments — instruct landlords on criminal screening and convey information about the risks of renting property to people with a criminal history.

Elements of Effective Strategies to Reduce Inflow from Incarceration

Ongoing community efforts to prevent and reduce inflow into homelessness among those exiting incarceration share fundamental strategies, which include formal cross-sector collaboration, inreach efforts to assess homelessness risk and housing needs in jail or prison, housing planning before release, and data collection, sharing, and monitoring.

Efforts to combat inflow from incarceration largely rest on building partnerships — and then, formal collaborations — between the housing and homeless response system and criminal legal system. Initial engagement could include establishing cross-sector representation in key planning bodies, such as CoCs, criminal justice advisory boards, and reentry councils. Once the conversations get started, a learning phase can take place. This might involve cross-system training to establish understanding of respective systems (each of which are complicated) and shared language, as well as regular meetings to build working relationships and establish contacts and have important discussions to identify shared goals, as well as respective resources and constraints.

Formalizing collaboration could involve documenting clearly defined roles in meeting shared goals within MOUs or other written agreements. Community partners should also formalize data-sharing protocols with written agreements that define the parameters of shared data use. As part of this process, local criminal legal and homelessness service system partners should map out available data sources, types, and processes and discuss any desired changes and sharing needs. This process is vital to facilitating data matching and taking stock of the size of the shared population and frequency of contacts with both systems.

Conducting screening, assessment, and housing planning in jails and prisons can play a significant role in reducing inflow from incarceration. Whichever screening and assessment instruments and methods are used, the process needs to be straightforward in order to be easily incorporated into correctional staff’s workflow before reentry or diversion. Existing tools, such as the National Reentry Resource Center’s screening questionnaire, can be implemented, or jurisdictions may create their own brief set of questions or draw on examples from local homeless assistance providers.13

Reentry coordinators, discharge planners, and other corrections system partners can collaborate with CoCs and community housing partners to establish a referral process. If resources permit, jails or prisons can be established as coordinated entry access points in the community, and service providers should be included in inreach efforts. Tracking referral outcomes can also enable communities to identify and bridge gaps in facilitating handoffs. For instance, the Connection to Care program in Long Beach, CA recognized that clients lacked direct modes of transportation upon release. Based on this, the program hired a transportation coordinator to arrange taxis to transport clients to services and procured funds for individualized transportation at release.14

In addition to sharing data across systems, jurisdictions should actively collect and monitor data capturing peoples’ housing and other service needs, how these are being assessed, and who’s being connected to resources. This invaluable data can be utilized to advocate for investments in affordable housing developments to increase supply and facilitate policy conversations around prioritizing formerly incarcerated people for existing housing. Moreover, this data should be collected in a manner that allows for disaggregation by race, ethnicity, and gender. This way, data can 1) demonstrate the demographic breakdown among people in jail or prison as compared to the larger community, 2) inform program staffing, and 3) be monitored to identify and address any disparities in assessment, referrals, and housing outcomes.

For evaluations of four innovative programs, click here.

Conclusion

Evidence demonstrates that people who have spent time in prisons or jails make up a considerable proportion of those experiencing homelessness in the U.S. For local and large-scale homelessness prevention efforts that aim to stop inflow in its tracks, targeting resources to support people exiting incarceration would likely be an effective and efficient strategy.

Many successful models of community efforts boil down to the same elements: cross-sector engagement, learning, and collaboration; data collection, sharing, and monitoring; assessing and planning to meet housing needs in jail or prison; and maximizing respective system resources to coordinate services and track outcomes.

Footnotes

- No Access to Justice: Breaking the Cycle of Homelessness and Jail. Vera Institute Report, 2020; Nowhere to Go: Homelessness among formerly incarcerated people. Prison Policy Institute, 2018.

- Incarceration & Reentry. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. ASPE, 2015.

- Christy A. Visher and Shannon M.E. Courtney. One Year Out: Experiences of Prisoners Returning to Cleveland. Urban Institute, 2007; Richard Peterson. Re-arrests of Homeless Defendants in New York City. New York City Criminal Justice Agency, 2016; Amanda Geller and Marah Curtis. A Sort of Homecoming: Incarceration and the housing security of urban men. Social Science Research 40(4), 2011; Katharine Bradley et al. No Place Like Home: Housing and the ex-prisoner. Community Resources for Justice, 2001.

- Stephen Metraux and Dennis P. Culhane. Recent Incarceration History Among a Sheltered Homeless Population. Crime & Delinquency, 52(3), 2006; New data: The revolving door between homeless shelters and prisons in Connecticut. Prison Policy Institute, 2021; Nowhere to Go: Homelessness among formerly incarcerated people. Prison Policy Institute, 2018.

- Presented by Liz Buck and Hallie Fader-Towe of the CSG Justice Center as part of the CCJBH Legislative Briefing, January 2019. Cited in the CCJBH’s Policy Brief on Improving Housing Outcomes for the Justice-Involved with Behavioral Health Challenges, January 2020.

- Robynn Cox et al. Does the timing of incarceration impact the timing and duration of homelessness? Evidence from “The Transitions to Housing” study. Justice Quarterly 38(6), 2021.

- National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction.

- Marie Claire Tran-Leung. When Discretion Means Denial: A National Perspective on Criminal Records Barriers to Federally Subsidized Housing. Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, 2015.

- Christy Visher, Nancy La Vigne, and Jill Farrell. Illinois Prisoners’ Reflections on Returning Home. Urban Institute, 2009.

- Out of prison & out of work: Unemployment among formerly incarcerated people. Prison Policy Institute, 2018.

- Evans & Porter. Criminal history and landlord rental decisions: a New York quasi-experimental study. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 2015; Lynn Clark. Landlord attitudes toward renting to released offenders. Federal Probation, 2007.

- The Cost of Being “Crime Free”: Legal and Practical Consequences of Crime Free Rental Housing and Nuisance Property Ordinances. Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, 2013.

- Assessing Housing Needs and Risks: A Screening Questionnaire, April 2022.

- Connection to Care in a Municipal Jail Setting: An Innovation Fund Case Study from Long Beach, California. Urban Institute, May 2021.

Works Cited

Research Reports and Articles

Nowhere to Go: Homelessness among formerly incarcerated people. Prison Policy Institute 2018.

New data: The revolving door between homeless shelters and prisons in Connecticut. Prison Policy Institute 2021

Incarceration and Homelessness. Metraux et al., 2007

Evans & Porter. Criminal history and landlord rental decisions: a New York quasi-experimental study. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 2015.

Lynn Clark. Landlord attitudes toward renting to released offenders. Federal Probation, 2007.

Tsai & Rosenheck. Incarceration among Chronically Homeless Adults: Clinical Correlates and Outcomes. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 2012.

Somers, et al. Housing First Reduces Re-offending among Formerly Homeless Adults with Mental Disorders: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE, 2013.

Christy A. Visher and Shannon M.E. Courtney. One Year Out: Experiences of Prisoners Returning to Cleveland. Urban Institute, 2007.

Richard Peterson. Re-arrests of Homeless Defendants in New York City. New York City Criminal Justice Agency, 2016.

Amanda Geller and Marah Curtis. A Sort of Homecoming: Incarceration and the housing security of urban men. Social Science Research 40(4), 2011.

Katharine Bradley et al. No Place Like Home: Housing and the ex-prisoner. Community Resources for Justice, 2001.

Evaluations

Pima County Housing First Initiative: Final Evaluation Report Fall 2021. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2021

Supportive Housing for Returning Prisoners: Outcomes and Impacts of the Returning Home-Ohio Pilot Project. The Urban Institute, 2012.

Breaking the Homelessness-Jail Cycle with Housing First: Results from the Denver Supportive Housing Social Impact Bond Initiative. Urban Institute, 2021.

An Evaluation of the New York City Housing Authority’s Family Reentry Pilot Program: Final Report to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Vera Institute of Justice, September 2017.

Reports and Case Studies of Specific Programs and Initiatives

Connection to Care in a Municipal Jail Setting: An Innovation Fund Case Study from Long Beach, California. Urban Institute, 2021.

Frequent Users System Engagement: Denver Supportive Housing Social Impact Bond Initiative. Case Study by the Corporation for Supportive Housing.

Webinars and Presentations

Stepping Up: Addressing Housing Needs of People with Mental Illnesses in Jails. Webinar hosted by The Council of State Governments Justice Center and the National Association of Counties, November 2017.

Cross-Systems Data Sharing in Practice: Homeless Services, Healthcare, and Criminal Justice. National Human Services Data Consortium, 2018.

How State-Led Housing Initiatives Can Break the Cycle of Criminal Justice Involvement. Webinar hosted by The Council of State Governments Justice Center and Bureau of Justice Assistance, September 2020.

Building Effective Partnerships with Continuums of Care to Increase Housing Options for People Leaving Prisons and Jails. Webinar hosted by The Council of State Governments Justice Center, the National Reentry Resource Center, and the Bureau of Justice Assistance, April 2022.

Thinking Outside the Box Housing Webinar Series: Cross-Sector Strategies to Create Housing Opportunities for People with Behavioral Health Needs Leaving the Justice. Webinar series hosted by The Council of State Governments Justice Center, Bureau of Justice Assistance, and Corporation for Supportive Housing. May-July, 2022.

- The Action Points Framework: Four Key Steps to Expanding Housing Opportunities.

- Prioritizing Housing Resources for People in the Justice System

- Key Development Concepts and Housing Models for Justice System Leaders

How One County Screens and C0nnects People in Jail to Housing. CSGJC 2022.

Policy Analyses, Reviews, and Other Policy-Centered Sources

Helping Moms, Dads, and Kids to Come Home: Eliminating Barriers to Housing for People with Criminal Records. Legal Action Center, 2016.

National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction.

Marie Claire Tran-Leung, When Discretion Means Denial: A National Perspective on Criminal Records Barriers to Federally Subsidized Housing. Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, 2015

The Cost of Being “Crime Free”: Legal and Practical Consequences of Crime Free Rental Housing and Nuisance Property Ordinances. Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, 2013.

No Access to Justice: Breaking the Cycle of Homelessness and Jail. Vera Institute Brief, August 2020.

Screened Out: How Tenant Screening Reports Undermine Fair Housing Laws and Deprive Tenants of Equal Access to Housing in Illinois. Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, 2021.

HUD Memo – June 10, 2022.

HUD Memo – April 12, 2022.

Other

Coming Home (A Justice-Involved Permanent Supportive Housing Program). Information on Durham’s Coming Home Program on the Resources for Human Development website.