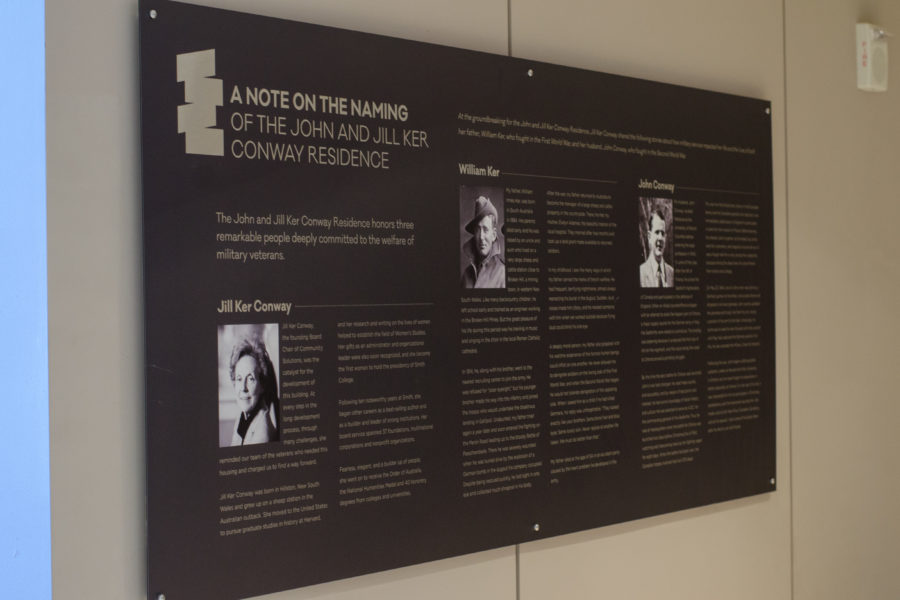

At the groundbreaking for the John and Jill Ker Conway Residence, Jill Ker Conway shared the following stories about how military service impacted her life and the lives of both her father, William Ker, who fought in World War I, and her husband, John Conway, who fought in World War II. Today this plaque hangs in the John and Jill Ker Conway Residence, a supportive housing residence for formerly homeless veterans in Washington, D.C.

Jill Ker Conway

Jill Ker Conway, the founding Board Chair of Community Solutions, was the catalyst for the development of this building. At every step in the long development process, through many challenges, she reminded our team of the veterans who needed this housing and charged us to find a way forward.

Jill Ker Conway was born in Hillston, New South Wales and grew up on a sheep station in the Australian outback. She moved to the United States to pursue graduate studies in history at Harvard, and her research and writing on the lives of women helped to establish the field of Women’s Studies. Her gifts as an administrator and organizational leader were also soon recognized, and she became the first woman to hold the presidency of Smith College.

Following 10 noteworthy years at Smith, she began other careers as a best-selling author and as a builder and leader of strong institutions. Her board service spanned 37 foundations, multinational corporations and nonprofit organizations.

Fearless, elegant, and a builder up of people, she went on to receive the Order of Australia, the National Humanities Medal and 40 honorary degrees from colleges and universities.

William Ker

My father, William Innes Ker, was born in South Australia in 1884. His parents died early and he was raised by an uncle and aunt who lived on a very large sheep and cattle station close to Broken Hill, a mining town, in western New South Wales. Like many backcountry children, he left school early and trained as an engineer working in the Broken Hill Mines. But the great pleasure of his life during this period was his training in music and singing in the choir in the local Roman Catholic cathedral.

In 1914, he, along with his brother, went to the nearest recruiting center to join the army. He was refused for “poor eyesight,” but his younger brother made his way into the infantry and joined the troops who would undertake the disastrous landing in Gallipoli. Undaunted, my father tried again a year later and soon entered the fighting on the Menin Road leading up to the bloody Battle of Passchendaele. There he was severely wounded when he was buried alive by the explosion of a German bomb in the dugout his company occupied. Despite being rescued quickly, he lost sight in one eye and collected much shrapnel in his body.

After the war, my father returned to Australia to become the manager of a large sheep and cattle property in the countryside. There, he met my mother, Evelyn Adames, the beautiful matron of the local hospital. They married after two months and took up a land grant made available to returned soldiers.

In my childhood, I saw the many ways in which my father carried the marks of trench warfare. He had frequent, terrifying nightmares, almost always reenacting his burial in the dugout. Sudden, loud noises made him jittery, and he needed someone with him when we worked outside because flying dust could blind his one eye.

A deeply moral person, my father also grappled with his wartime experience of the horrors human beings could inflict on one another. He never allowed me to denigrate soldiers on the losing side of the First World War, and when the Second World War began, he would not tolerate denigration of the opposing side. When I asked him as a child if he had killed Germans, his reply was unforgettable. “They looked exactly like your brothers. Same blond hair and blue eyes. Same lovely skin. Never rejoice at another life taken. We must do better than that.”

My father died at the age of 54 in an accident partly caused by the heart problem he developed in the army.

John Conway

My husband, John Conway, studied literature at the University of British Columbia before entering the legal profession in 1940. In June of that year, after the fall of France, he joined the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada and participated in the defense of England. When an Allied counteroffensive began with an attempt to seize the Aegean port of Ortona, a major supply source for the German army in Italy, the Seaforths were elated to contribute. The landing was sobering because it produced the first loss of life for the regiment, and the route along the coast to Ortona proved a grinding struggle.

By the time the epic battle for Ortona was launched, John’s role had changed. He read maps quickly and accurately, and by reason of education and interest, he had some knowledge of Italian history and culture. He was selected to serve as A.D.C. for the commanding general of the Seaforths. Thus, he was at headquarters when the battle for Ortona was launched two days before Christmas Eve of 1942, watching and interpreting news as the fighting raged for eight days. When the battle had been won, the Canadian troops involved had lost 1375 dead.

This was the first Allied land victory in the European arena, and the Canadian general who had led it was immediately called back to England to participate in plans for the invasion of France. Before leaving, he ordered John to gather up the dead, buy some land for a cemetery, and organize a burial service. It was a tough task for a very young man, especially because among the dead were his close friends from school and college.

On May 23, 1944, one of John’s men was shot by a German gunner on the Hitler Line outside Rome and dropped a live hand grenade. John quickly grabbed the grenade and flung it far from his unit, losing a portion of his arm to the blast. Amazingly, he continued to lead his men forward with only a pistol until they had captured the German position. For this, he was awarded the Military Cross for heroism.

Following the war, John began a distinguished academic career at Harvard and York University in Ontario, but he never forgot his experience in battle, especially at Ortona. For the rest of his life, it was impossible for him to participate in Christmas celebrations, and the memories haunted him. We made visits to the Moro River Canadian Cemetery, and at his request, I took some of his ashes there after he died to join old friends.