What do you think when you see someone living on the street? Some people see homelessness as a crime. Moki Macias sees someone who needs help.

It can be difficult for community members to understand “just how vulnerable and how visible people are when they don’t have a house … Some of what people may be getting caught up in is directly related to the strategies that they are using to survive homelessness,” explained Macias.

That’s why Atlanta, a Built for Zero community, is working differently. Instead of criminalizing homelessness, the community is using law enforcement’s help to divert people from the criminal justice system and connect them to resources instead.

The Supreme Court recently determined that U.S. cities can punish people for experiencing homelessness. Criminalization doesn’t solve homelessness — it only makes it harder to escape. Innovations like Atlanta’s diversion program provide better solutions for homelessness.

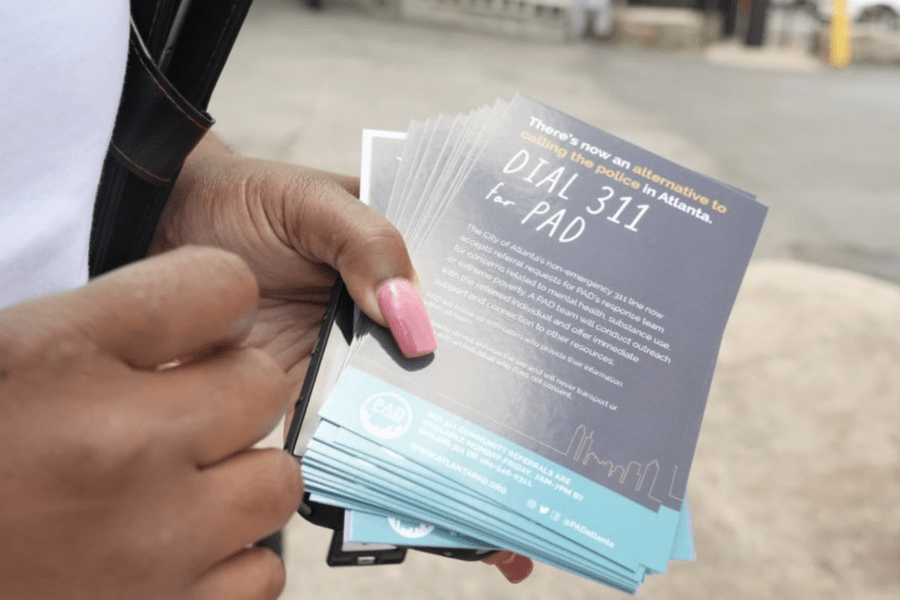

Macias is the Executive Director of the Policing Alternatives and Diversion Initiative (PAD), a program designed to intervene in situations where people experiencing homelessness would otherwise be arrested. PAD responds to community concerns related to mental health, substance use, and extreme poverty. It provides an alternative to incarceration for people who commit minor violations often tied to homelessness and instead connects them with services.

Thanks to innovative approaches like this, Atlanta housed over 2,000 people experiencing homelessness in 2023, 800 of whom were unsheltered.

Responding to homelessness with community response teams instead of police

Police are trained to enforce the law, but they’re not equipped for homeless response. Yet, “they’re under extreme pressure from community members, business owners, elected officials to show up and make people ‘disappear,’” said Macias.

The PAD initiative began in 2017 and grew out of a campaign fighting a banishment ordinance targeting sex workers in Atlanta. Today, it runs the pre-arrest diversion program based on a successful program in King County, Washington.

Here’s how it works: when law enforcement engages someone and has probable cause to arrest them for quality of life concerns that constitute low-level violations like loitering, shoplifting, or trespassing, they can instead call PAD to intervene. PAD’s street outreach workers will have a conversation with the individual to help get their most immediate needs met, like providing adequate clothing and a meal. They will help the individual complete an intake assessment for a local housing provider and ensure they have an immediate place to stay.

In 2021, PAD expanded its response to include community calls made through Atlanta’s 311 line, a dedicated line for community members to reach non-emergency services.

PAD also prioritizes those who are actively justice-impacted and offers care navigation for people who already have active cases. When some individuals get arrested, but prosecutors see they need resources, such as mental health support or shelter, people can be released to PAD directly and won’t have charges held against them for that arrest so long as bail has not been set. Once released, they are free to leave if they choose.

You don’t need to be experiencing homelessness to get help from PAD. Still, about 95% of people who get connected to the service are experiencing homelessness.

As many as 30% of bookings into Atlanta’s detention facility are for charges associated with homelessness, according to a City of Atlanta press release from 2021. “I think that law enforcement recognizes that they have been a catch-all response for a very long time,” said Macias.

The initiative can divert arrests both before and after an arrest takes place. In March 2024, PAD diverted 40 arrests, 70% of which were after the arrest had taken place. By far, the most common charge was criminal trespass. The initiative responded to 184 calls through the 311 line. Its average response time for the month was 24 minutes. Over 148 participants have been enrolled in PAD’s Care Navigator program this year alone.

“I think that law enforcement recognizes that they have been a catch-all response for a very long time.”

— Moki Macias, Executive Director of PAD

The new Center for Diversion Services is expected to open in September 2024. The 24-hour facility will be a central place where law enforcement and first responders can drop off individuals for violations driven by extreme poverty, unaddressed mental illnesses, and substance use. People can receive food, clothing, showers, and case management. They are also free to leave if they do not consent to receiving services at the Center and can re-engage with PAD if they change their minds later on. There will also be a sobering center, medical screenings, and appointments on-site. Participants can stay for up to 24 hours at a time. They can be diverted to the Center an unlimited number of times.

The Center will be managed by Grady Health, and PAD will be among other agencies offering services.

Lilly’s path to housing

Lilly Gaskin first experienced homelessness over a decade ago. After her initial experience with homelessness, she eventually found herself without an ID and no real means of replacing it.

“People get into the situation of homelessness for all kinds of reasons. It’s not because they’re on drugs or they’re too lazy to work,” she said. “People can get sick and can’t work, or their paperwork can get lost in a fire. There’s a lot of things that can happen that can qualify people to be considered homeless.”

“People get into the situation of homelessness for all kinds of reasons. … There’s a lot of things that can happen that can qualify people to be considered homeless.”

Lilly Gaskin

During that period of her life, she was arrested in different circumstances. She had two children and struggled to maintain housing after multiple placement attempts.

She eventually was connected with PAD, who matched her with her care navigator, Victoria Hull. Communication was limited because Gaskin didn’t have a phone connection and relied on Wi-Fi to contact people. This caused her to miss four assessment interviews, which are meetings that help providers figure out exactly what support an individual experiencing homelessness needs. At this point, Hull “came to me where I was at that exact moment. She brought me some groceries,” said Gaskin. “We made a goal sheet of what I wanted to accomplish.”

Hull placed Gaskin into coordinated entry with Partners for Home, the organization that oversees collaboration across Atlanta’s Continuum of Care (CoC), which then placed her into rapid rehousing with Zaban Paradies Center, a local shelter that serves families and couples experiencing homelessness. This February, she moved into her own apartment.

“Victoria has been the greatest. If I needed her for anything, she was always available,” said Gaskin. “She doesn’t belittle me or embarrass me. She gave me the strong help I needed, because I don’t have that in my family. It’s just me and my babies.”

Gaskin is one of the 1,200 people experiencing unsheltered homelessness who has been connected to housing in Atlanta since 2022, thanks to support from PAD.

Familiar Faces helps identify those facing frequent arrests and connects them to support

The Familiar Faces Project, led by the Fulton County Superior Court, helped identify 100 individuals who are arrested most frequently and uses collaborative data management and case tracking to help providers in the homeless response system, like PAD, identify them and offer them the support they need.

Those people identified commonly struggled with homelessness and mental health issues. These 100 people were 10 times more likely to be booked into jail than the average detainee and accounted for 20 times the number of days in jail.

One reason for this is that someone cannot be released from jail to await their next court hearing unless they have an address. “Once they get into jail, it makes release so much more complicated for people without housing,” explained Kristin Stoycheff Schillig, the Planning and Development Director of the Superior Court and the coordinator for the Familiar Faces Project.

To address challenges around pretrial release for those who can’t afford bail, Fulton County Superior Court and their justice partners have been working with public policy philanthropy Arnold Ventures and the Advancing Pretrial Policy and Research Project. “Release should be the norm,” she said. “We want our judges to rely on these collaboratively developed approaches, release decision tools and objective information to make more informed decisions that allow people to come back to their next court hearing without being incarcerated whenever possible.”

Compassionate encampment closures

Partners for Home has worked to house over 1,500 people in 2024 so far, thanks to lines of funding that were created during COVID-19, as well as strategic partnerships.

One innovation has been around rapid rehousing. Rapid rehousing is a solution to homelessness designed to help individuals and families quickly exit homelessness and return to permanent housing by offering flexible, time-limited assistance. It is offered without preconditions (such as employment, income, absence of criminal record, or sobriety) and the resources and services provided are typically tailored to the unique needs of the household.

“Atlanta police have really continued to impress me. They will say that homelessness is not a crime and that we can’t arrest our way [out of] this situation.”

Cathyrn Vassell, CEO of Partners for Home.

At Partners for Home, instead of each provider doing every component of rapid rehousing, like finding housing units, case management, and rental assistance, providers instead specialized in one area and collaborated on cases. Thanks to this approach, last year, they were able to permanently house 800 people experiencing unsheltered homelessness.

The organization’s Encampment Closure Plan creates a way to compassionately engage with residents, connect them with relevant resources, and offer transportation to those resources when an encampment is decommissioned. Taken together, these efforts are meant to give people options so they won’t need to return.

By fostering a positive relationship with police, homeless service providers can be accompanied by police only as needed as they build relationships with encampment residents. “They go out with us in certain instances where we anticipate or have reason to believe that safety might be a concern,” said Cathyrn Vassell, CEO of Partners for Home. “We try not to over-rely on them.” Police will monitor the area where an encampment has been cleared to redirect attempts to resettle back to the Partners for Home outreach team.

“Atlanta police have really continued to impress me,” said Vassell. “They will say that homelessness is not a crime and that we can’t arrest our way [out of] this situation.”

Right now, street outreach is focusing particularly on closing encampments located under bridges after the integrity of a bridge was compromised by a fire, which was believed to have been set by a person experiencing unsheltered homelessness trying to stay warm. After the fire, outreach workers, police, and workers from the Georgia Department of Transportation engaged the half dozen residents at the site, who moved to a temporary shelter.

Working with people experiencing unsheltered homelessness has “reinforced what we already know, that homelessness is a housing problem. One of the big misconceptions is that people who are unsheltered ‘don’t want help,'” said Vassell. “It’s a matter of building trust and rapport with an individual so they actually believe that a housing solution is forthcoming. Overwhelmingly the majority of people that we connect with are very interested in housing.”