This is not the first time the Gulf Coast Region in Mississippi has faced a crisis. The circumstances are very different, but when Hurricane Katrina destroyed 92 miles of coastline in 2005 and displaced more than 100,000 people, the community went into action and collaborated together to build solutions. Now they’re doing the same during the COVID-19 crisis.

“Everyone is reviewing the Katrina playbook and tweaking as necessary,” said Mary Simons, Executive Director and CEO of Open Doors Homeless Coalition.

Built for Zero includes communities that believe that in order to end homelessness, it must be treated like the public health crisis it is. These communities have brought together all the actors who work on homelessness in a command center style structure, with a commitment to get to zero. Using real-time data, they quickly test ideas for systems improvements — a discipline adapted from health care — with the goal of reducing the overall number of people experiencing homelessness. They had to shift their strategies nimbly as conditions on the ground changed and solve for whatever problems might arise. During the pandemic, this reliance on partnerships and command center models have been elevated to make unprecedented activities possible.

“We didn’t know it, but all of that work was training for this crisis,” said Jake Maguire, Co-Director of Built for Zero.

“Everyone is about ‘get people inside.’ We know that inside is permanent housing.”

— Mary Simons, Executive Director and CEO of Open Doors Homeless Coalition

Bringing all hands on deck

In the Gulf Coast region of Mississippi, a solid network of various agencies and partners has allowed Simons’ team to continue their work during the pandemic.

“The partnerships we’ve built along the way have been very, very helpful,” Simons said.

By working with the local business council, Simons is working to secure a hotel to bring more unsheltered people inside. And while their outreach staff shelter in place, they’ve been able to lean on a long-time partner: the local police department. Officers began reaching out to people without shelter to help get them to safety. The police have offered transportation to people who need to get to shelter and have even checked out housing, where inspections were needed.

“The police department has done a good job in picking up that slack for us,” Simons said. “That was in direct response to us having built those relationships.”

In Colorado Springs, Colorado, the homeless response team has forged a partnership with the University of Colorado School of Medicine to set up a telehealth “Med Line,” where medical students and an assistant dean are on hand 24 hours a day to answer COVID-19 questions that may come up with clients.

“Since most of the med students and faculty are at home they had time and they had resources,” said Jennifer Mariano, Director of Homeless Programs at Community Health Partnership. They also tapped on the medical school to work with their department of public health to create algorithms to help determine who would be safe to admit to shelter and how to transport clients safely to isolation.

In Vermont, partnerships have come together to test people experiencing homelessness for COVID-19. Because many people experiencing homelessness in the largely rural state lack transportation, the local team acted quickly to create a mobile testing center operated by a community health center. A retrofitted van serves as the testing facility, traveling throughout Chittenden County.

“Ten days after that idea was thrown out, we now have a mobile testing center,” said Jason Brill, a social worker at the Vermont VA. “Now lots of people are able to get tested.”

Creating new leadership structures

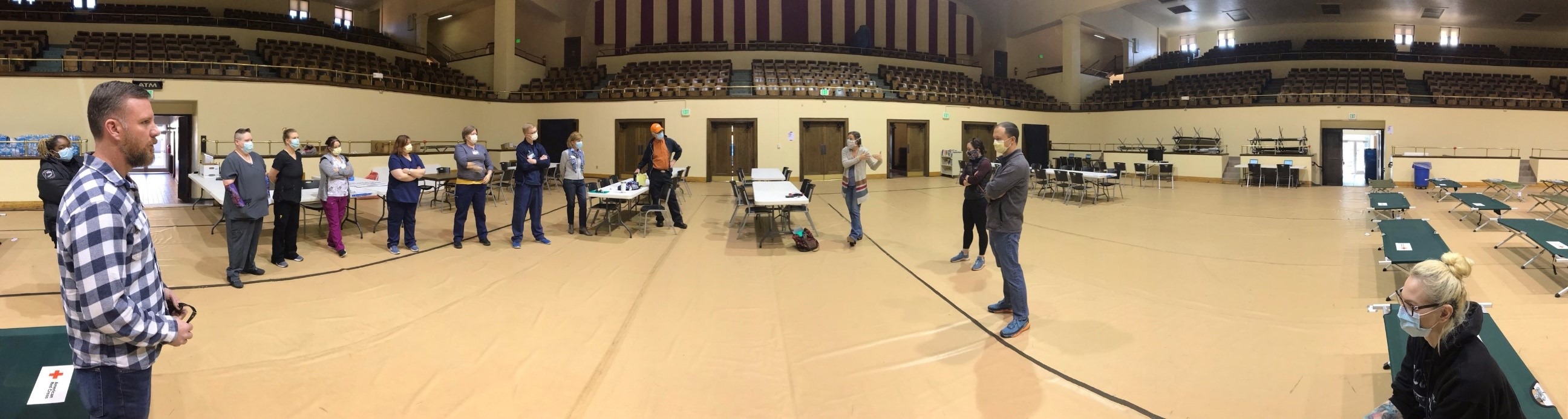

Crisis response calls for command center structures, and states, cities and counties have responded accordingly by forming cross-sectoral leadership and decision-making structures. They most often include representatives from local government, public health departments, and different agencies to coordinate their community response, which include supporting and protecting the homeless population.

In Jacksonville, Florida, a core group of about 15 people are responsible for the city’s isolation and shelter response. In Winston-Salem, North Carolina, the local continuum of care is working with the County’s Department of Public Health, Department of Social Services, and the City to execute a four-part plan to address the needs of people experiencing homelessness.

“It’s not something that the homelessness system can handle alone,” said Katy Miller, Regional Coordinator at the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. “All of the resources in the community need to come to bear.”

In the Seattle area, the Public Health-Seattle & King County, Department of Community and Human Services, Facilities Management Division, Office of Emergency Management, and METRO employees are working together alongside the city and a network of partner providers. This team is operating seven days a week to create a new network of facilities and services to slow the spread of COVID-19.

“Once we come out of this crisis, it’s really important that the cross-sector responses continue. There has to be a way to leverage these relationships to ensure safe and healthy housing for everyone in the community,” Miller said.

Leveraging new partnerships

The public health response to coronavirus has created alliances between groups and organizations that typically don’t collaborate. In Madison, Wisconsin, the continuum of care has partnered with local hotels to establish isolation and quarantine space for people experiencing homelessness. Torrie Kopp Mueller, the CoC Coordinator, explained that one challenge was educating hotel staff.

“I wasn’t expecting the amount of time spent managing hotel expectations and helping the staff feel at ease with having people experiencing homelessness come into their space,” Mueller said.

To respond, the Madison team assigned a staff member to develop relationships with hotels and secure additional rooms. They also contracted with a behavioral health organization, in order to provide additional case management services for clients living at the hotels.

“I feel like every day there’s a new curve ball thrown at us,” Mueller said. But their efforts with hotels are paying off: Mueller reports that hotels are increasing the number of rooms available for people experiencing homelessness. Currently they’ve housed more than 180 people in hotel rooms, including 51 households with children.

In Gulf Coast, Mississippi, Simons sees this pandemic as an opportunity to bring in more partners to work toward ending homelessness.

“My encouragement is: build on the partnerships you have, particularly partnerships that are outside the homeless services sector,” Simons said. “Embrace these partnerships even if the ideas are different than what you might have.”

“Everyone is about ‘get people inside.’ We know that inside is permanent housing. It doesn’t matter what our partners’ why may be; our why is that it’s the right thing to do,” Simons said.