The upcoming Johnson v. Grants Pass Supreme Court hearing on April 22 will weigh whether the Eighth Amendment protects homeless citizens from efforts to criminalize their existence.

The case will determine if it’s cruel and unusual punishment to ticket and arrest citizens for sleeping in public spaces, even if they have nowhere else to go.

This is the most significant Supreme Court case about homelessness in 40 years. We surveyed 170 leaders across communities in the Built for Zero movement to learn the impacts of criminalizing homelessness — and find out what actually works to solve homelessness.

About Johnson v. Grants Pass

Grants Pass, Oregon, has a population of roughly 40,000 people. Like the overall U.S. population, about half of those living there struggle to pay rent. There are anywhere from 50 to 600 people experiencing homelessness in the city.

The city adopted anti-camping ordinances that penalize people who have no other place to go with fines of up to several hundred dollars per violation.

At the time the case was filed, there was only one transitional housing program in the city. The main intervention for men, women, and families is the Gospel Rescue Mission, a religious organization that provides housing if you commit to working six hours a day, six days a week, and pay $100 per month.

Despite a lack of alternatives, Grants Pass issued tickets and fined individuals for violating city ordinances with the express purpose of forcing homeless people to leave the city limits. Police fined people for sleeping in their cars or for sleeping in public spaces using a blanket, pillow, or sleeping bag. While a 2018 ruling decided that this was a form of cruel and unusual punishment, the case is now in the Supreme Court’s hands.

Arresting and ticketing people makes it harder to escape homelessness

In survey responses, Built for Zero leaders reveal just how common ticketing, arrests, and other criminalizing acts are used as a means to address homelessness. Just under half of all respondents say their communities use these tactics.

The impacts of tactics that criminalize homelessness

We surveyed 170 leaders across communities in the Built for Zero movement. Here’s what they said.

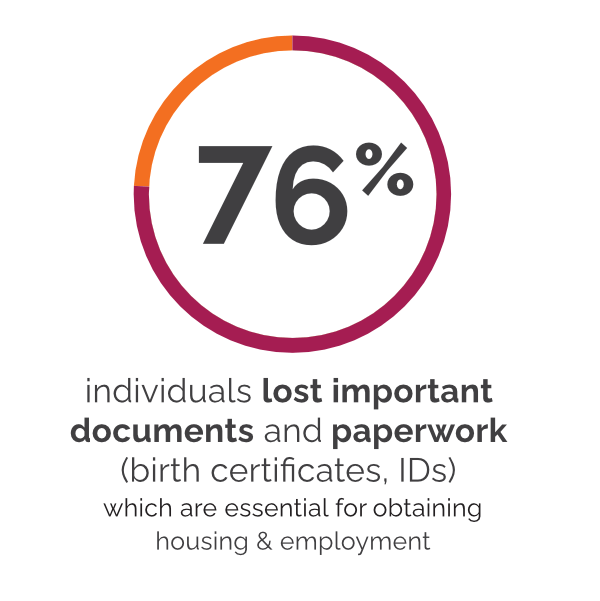

Actions include confiscating or discarding properties and scheduled encampment sweeps. Because of the sweeps, 76% of community leaders say those experiencing homelessness lost birth certificates or IDs, which are required to obtain employment and housing.

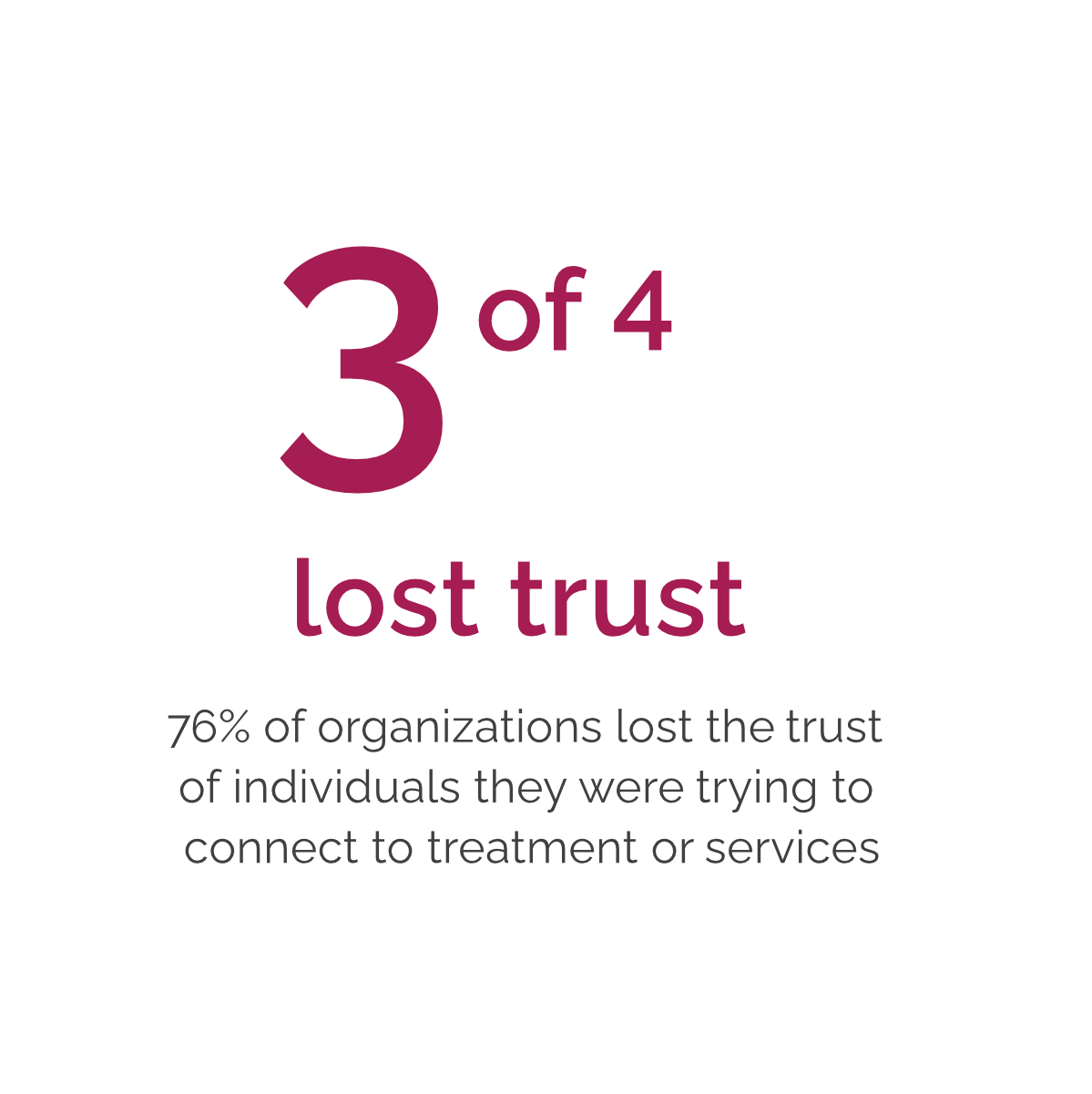

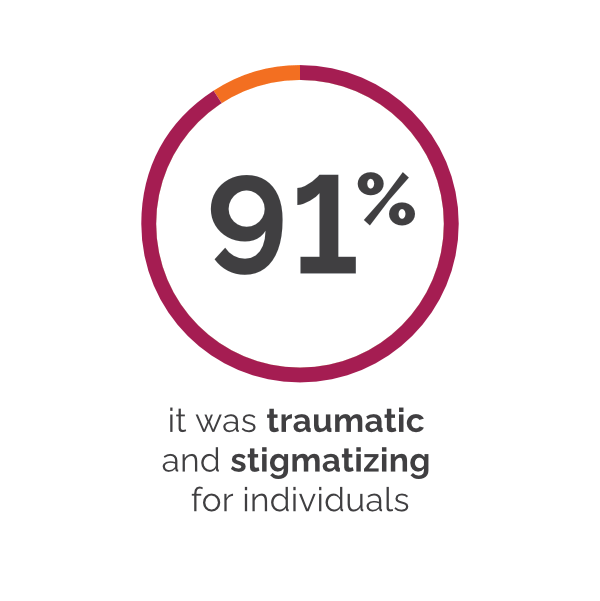

Criminalization adds to the trauma of experiencing homelessness and makes it harder to establish trust within the community. The overwhelming majority of respondents, 91%, say the actions were traumatic and stigmatizing for individuals who are unhoused. In 76% of communities, those in need of services lost trust in the organizations trying to work with them as a result of the criminalization of homelessness.

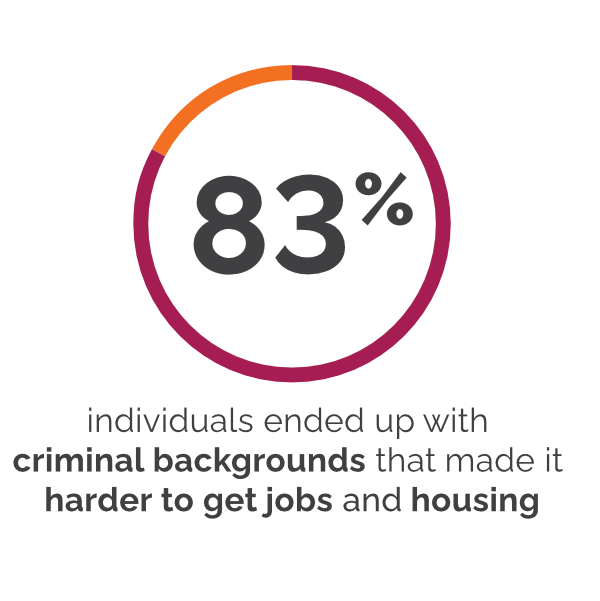

It also creates a direct barrier to housing. Eighty-three percent of respondents say people ended up with criminal records that made it harder to get jobs and housing, because of background checks.

One example, cited in a friend-of-the-court brief, illustrates how disruptive arrests can be to homeless response systems’ work to house people. In Nashville, a man was arrested 198 times and received over 250 charges for petty offenses in his 20 years of experiencing homelessness. An outreach worker struggled to make appointments for him due to his frequent arrests. She made him a t-shirt that said “please do not arrest me, my outreach worker is working on my housing.” After the man had stable housing, he had no additional encounters with the police.

Criminalization efforts can also separate families, as 39% of communities reported. Sarah Eastberg, an employment services manager who works with families and children in Nevada County, California, reveals that “because [families] have to go outside the city limits to sleep, they often have to park in areas that are not safe. The children are those who suffer, sometimes separated from their families.”

Judith Brown, Executive Director of Project 70Forward from Charlotte, North Carolina, revealed their city “is now ticketing people for ‘behavioral’ infractions, such as sleeping, urinating, etc. in public,” which will likely disproportionately affect those with disabilities. In Charlotte, around 40-50% of people who seek support with homelessness or imminent risk of homelessness are people with disabilities, they note.

Better solutions to homelessness

Tactics like tickets and arrests aren’t an effective solution to homelessness. But cities across the country are seeing homelessness go down with other interventions. Some places are approaching it like a public health crisis or disaster — with a coordinated, data-driven effort.

Collaboration

Effective collaboration among community organizations is key to solving homelessness. By unifying the efforts of all the organizations focused on homelessness, cities can establish a comprehensive, community-wide initiative that connects people to the resources they need to get into housing.

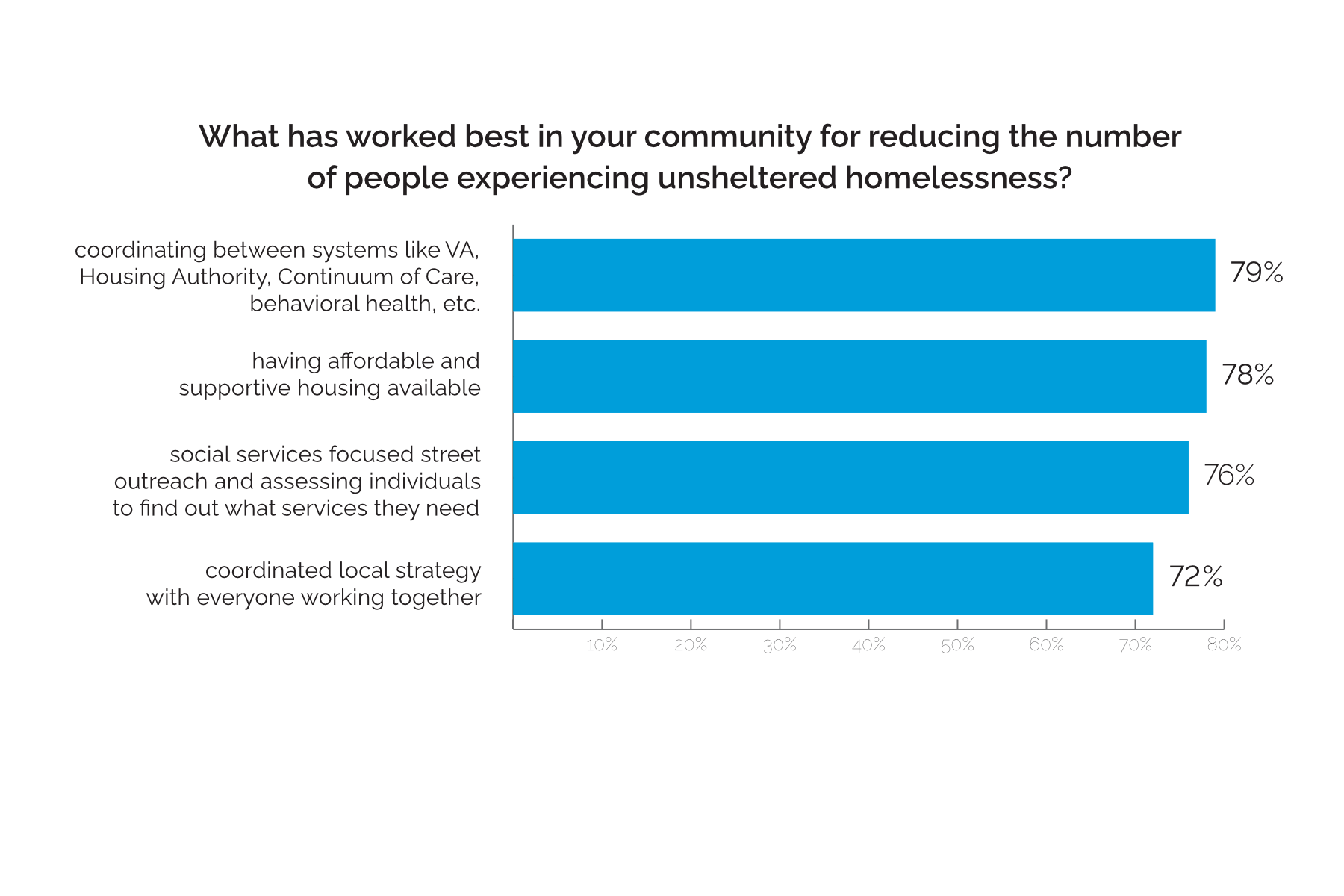

Seventy-nine percent of communities say coordinating between systems like the VA and mental health services helped reduce their numbers, and 72% saw improvements from a coordinated local strategy with everyone involved.

Data

Data can power solutions. Getting comprehensive data on exactly who is experiencing homelessness can help communities understand the scope of the issue. By-name data plays an essential role in mitigating homelessness, with 65% of leaders saying it played a role in reductions within their communities.

But many places, like Grants Pass, don’t have real-time data on who is experiencing homelessness. Without this data, it’s impossible to understand the true extent of homelessness in a region, making it much harder to accurately identify and close gaps in resources. Closing availability gaps can change outcomes — roughly three-quarters of leaders surveyed say having affordable and supportive housing, as well as having shelter beds available, makes a difference.

“The escalating unhoused population is due to a lack of affordable housing, not failings of individuals,” says Jacqueline Peigare, who works in homeless response in Nevada County, California. “We need to change the narrative that blames people for systemic problems and raise awareness that housing is a human right.”

Targeted investments

By getting a more accurate measurement, communities can make the right kinds of investments to serve the needs of a population. In the short term, investments can get people off the streets sooner or stop them from entering homelessness in the first place. Data can also help inform what types of additional services some might need to stay stably housed. Taken together, this puts communities on the path to making homelessness rare and brief.

“Our community stopped using punitive interventions and started investing in more temporary and permanent housing options about 14 years ago,” says Pamela Qualls, Secretary of the Board for the Homeless Leadership Alliance of Pinellas County, Florida. “The trend in our homelessness, except for anomalies during difficult times, has been downward.”

Johnson v. Grants Pass

Criminalization doesn’t solve homelessness — it only makes it harder to escape.