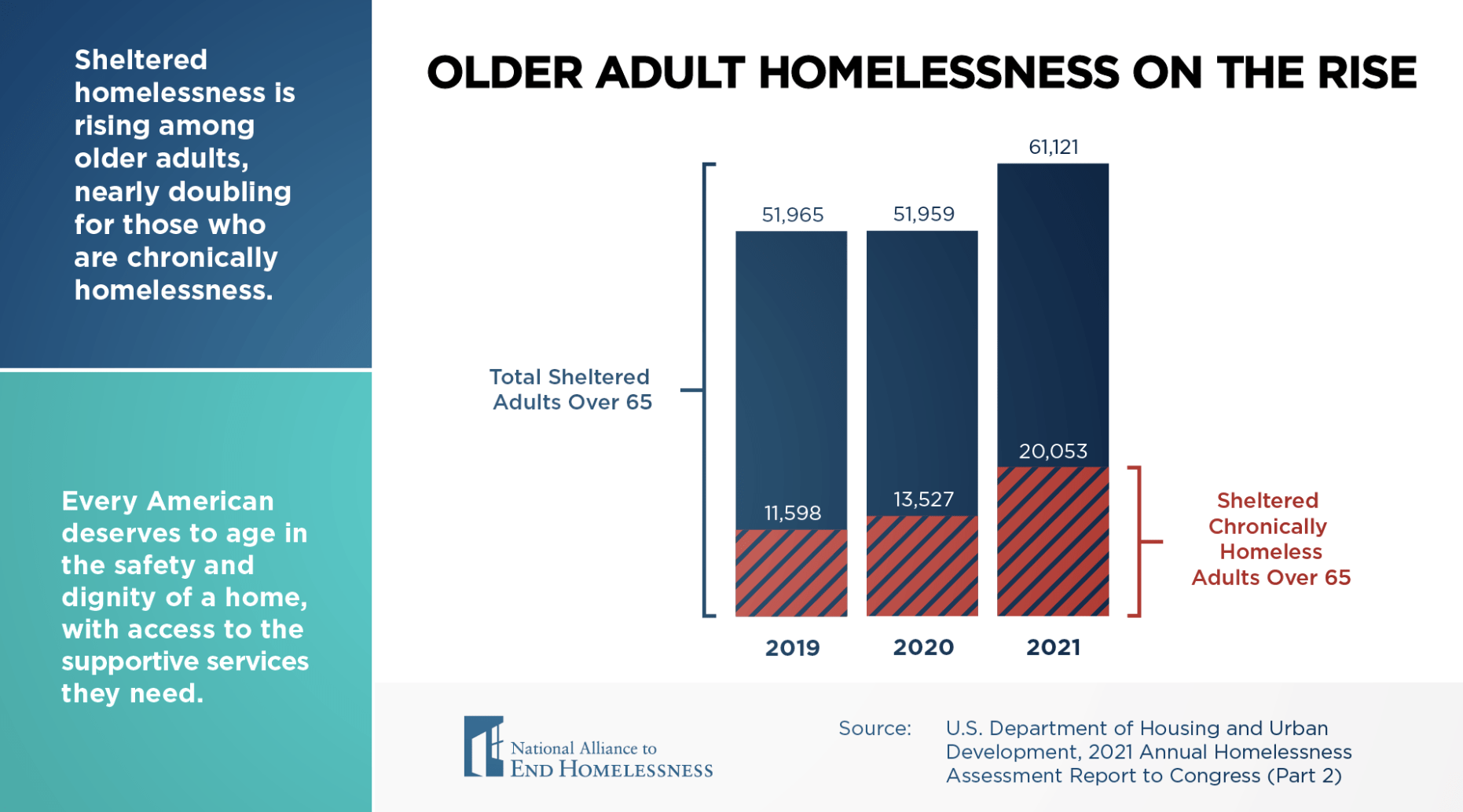

The United States is undergoing a profound demographic shift. By 2030, the Census Bureau predicts that one in five Americans will be aged 65 or older (Vespa, Medina, & Armstrong, 2018). With this shift comes an alarming increase in the number of older adults experiencing homelessness.

Older adults are at greater risk of experiencing homelessness today than at any point in recent history. In the 1990s, an estimated 11% of single adults experiencing homelessness nationally were ages 50 or older. By 2003, that number rose to 37%. By 2020, approximately half of homeless single adults were aged 50 or older, and projections estimate that the older homeless population will reach 225,000 by 2030 (Culhane et al., 2019).

Key Context and Causes

The forces contributing to elevated rates of homelessness among older adults are complex, but here are a few high-level causes:

- The aging baby boomer generation: People born in the second half of the baby boom have faced a greater risk of homelessness throughout their lives due to a series of economic recessions, high youth unemployment rates, mass incarceration policies, and stretched social safety nets, among other contributing factors (Culhane et al., 2013; Grabenstein, 2023). As this generation has aged, so has the older adult population experiencing homelessness.

- Declining homeownership rates: Declining rates of homeownership among older age groups means fewer older adults experience the additional housing security, more predictable housing costs, and the chance to build equity afforded by homeownership (JCHS, 2019). This shift has left more older adults in the rental market, where they can face rent increases and the risk of eviction.

- High housing costs, unattainable affordable housing, and rent burden among older adults: Rising housing costs and rent burden hit older adults who are no longer working on living on Social Security hard, forcing a high proportion of older adults to allocate a significant portion of their income to housing (Prunhuber & Kwok, 2021). Affordable housing, often designed for tenants earning between 50 and 80 percent of an area’s median income, is largely unaffordable for senior individuals living on a fixed income, Social Security, or other support.

- Lack of assisted living centers: Assisted living centers, specifically those built to be affordable and accessible, have been closing, and many of those remaining open are experiencing staff shortages or skyrocketing costs that require raising prices.

Pathways into Homelessness among Older Adults

Many older adults experience a rapid pathway into first-time homelessness, often triggered by abrupt life changes like the death of a partner or medical emergency (Om et al., 2022). These individuals have often led a relatively conventional life until a series of unexpected setbacks resulted in a sudden shift toward housing instability (Shinn et al., 2007; Om et al., 2022). Those who experience homelessness for the first time after the age of 50 are often unfamiliar with the homeless response system and available resources.

Another group of older adults experiencing homelessness has endured long stretches of homelessness throughout their lives. Early onset homelessness among this group is associated with lower attainment of adult milestones such as marriage and full-time employment. These older adults also tend to have had more adverse childhood experiences, mental health and substance use issues, and periods of incarceration (Brown et al., 2016).

Unique Challenges for Older Adults Experiencing Homelessness

Homelessness is especially harmful for older adults who experience unique burdens, including:

- Premature aging: Older adults experiencing homelessness in their fifties experience geriatric conditions, including sensory, mobility, and cognitive impairments, at a rate higher than housed adults in their seventies (Brown et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2017).

- Chronic health conditions: Older adults experiencing homelessness are more likely to have chronic conditions compared to younger adults experiencing homelessness (Garibaldi, Conde-Martel, & O’Toole, 2005).

- Functional impairments: Challenges with daily activities like bathing and dressing often require specialized medical care that is not available in traditional shelter settings (Canham et al., 2020).

- Traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis (Stubbs et al., 2020) found a 53% prevalence of traumatic brain injury in the homeless population due to several factors including childhood trauma, violence and substance use. This can be missed in the population and has an important impact on vulnerability and decision making.

Impact on the Homeless Response System and Other Sectors

The growing number of older individuals experiencing homelessness presents challenges for homeless response systems and other sectors. Older adults who have spent significant time on the street or in the shelter system often have complex health challenges related to those conditions. However, most shelters do not have facilities to accommodate older adults with complex health problems and are not built with accessibility in mind. Most shelters are ill-equipped to accommodate wheelchairs or low-mobility individuals, and many utilize bunk beds to be economical with their limited space.

The growing population of older individuals experiencing homelessness brings an increased demand for senior-specific housing programs and supportive services that may not resemble traditional offerings in layout or design. A survey held through the San Diego Regional Task Force on Homelessness in 2023 found that over 8,500 people age 55 or older participated in a supportive service in a given month, yet only 190 of those individuals found housing.

In addition, older adults with complex medical care needs often require safe and reliable spaces for recovery following surgeries or procedures. Unfortunately, recuperative or respite care facilities are often scarce or unaffordable. For example, if an individual requires a hip replacement from extended time sleeping in a vehicle or on the street, a hospital system may not be able to perform such a procedure because that individual would need a facility that does not exist locally or is unaffordable on social security or a fixed income.

Aging adults experiencing homelessness may also be declining in a way where they qualify for hospice care, but this can be missed in the complexity of the presentation of their social needs (Klop et al., 2018). Considering their unique needs and preferences near the end of life is important. Hospice and palliative care services are not widely integrated into the homeless response system, and this is an opportunity for expansion.

How can my Continuum of Care or community diagnose the severity of this issue?

Dig into the data: Assess the demographics of applicants for rental assistance programs or housing stability programs. How many of these individuals are over 55? What kind of complex medical care might they require?

Ask other systems: Connect with your local hospital system or Healthcare for the Homeless center to understand the trends and challenges they’re seeing with a similar population.

Open the dialogue: The aging of the homeless population has been a gradual process that many dedicated frontline workers have noticed but hardly had time to discuss or unpack outside of their organization. Creating a space or series of conversations for providers to discuss and process what they’re seeing can be transformative in building will and collective action.

Tap into existing services for older adults: There are many organizations like AARP or the Administration for Community Living, local Area Agencies on Aging, and even established teams within state and local departments of health that specialize in programming for aging adults. Explore conversations with these local stakeholders to get a sense of what they’re seeing, hearing, and planning.

Addressing and Preventing Homelessness among Older Adults

Addressing homelessness among older adults requires multifaceted interventions encompassing prevention, case management, outreach, and permanent supportive housing that are tailored to address the unique needs of older adults experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

Promising Prevention Programs

Prevention efforts, such as those examined by Community Solutions’ Housing Stabilization Learning Cohort, are nuanced and complex but can play a critical role in promoting positive health and housing outcomes for older adults experiencing or at risk of homelessness. Some notable initiatives and approaches include:

Shallow Subsidy Programs: Establishing permanent shallow subsidy programs can significantly improve housing stability for older adults, many of whom live on fixed incomes. A survey in San Diego County found that subsidies as little as $300 or less a month could make the difference needed for older adults to remain housed and avoid homelessness (Serving Seniors, 2021).

Hearth’s Outreach Program: Hearth, a nonprofit based in Boston, combines outreach and permanent supportive housing to combat elder homelessness. The outreach program’s team of case managers identifies individuals aged 50 and above experiencing or at risk of homelessness through shelter visits and referrals. Case managers provide assistance in securing safe and affordable housing, connect clients to critical health and social services, support housing stabilization, and help clients build social networks in the community. Hearth also has prevention case managers who provide services including landlord medication, money management, and shallow subsidies to prevent eviction. In 2021 alone, Hearth successfully prevented homelessness for 81 seniors and safely moved 100 individuals into affordable housing.

The Aging Right in Community Initiative: This collaborative effort between Boston Medical Center’s Elders Living at Home program and the Medical-Legal Partnership Boston provides legal expertise and intensive case management to older adults aged 55 and above at imminent risk of homelessness. The team addresses housing-related issues such as rent arrears and home safety concerns, aiming to resolve them through negotiations with landlords and connecting clients to appropriate health and social services. The initiative has been highly successful, preventing homelessness for at least 91% of clients in its first three years, with 96% remaining housed at the end of year three (Flacks et al., 2016).

Going Upstream in Your Community

Outreach and Assessment: Through a quick stakeholder analysis in your community, consider who might be connected to aging and senior adults who could be at risk of homelessness.

Here are a few ideas:

- Talk to the leader and drivers for the local Meals on Wheels program who distribute meals to seniors on a daily basis.

- Talk to the local department of social services or aging populations to see what they’re working on.

- Ask your local United Way about the Emergency Food and Shelter National Board Program.

- Engage local community-based organizations and faith-based organizations that play a key role in many of these individuals’ lives.

There’s no wrong answer here, and every community has different stakeholders – but find those that work with this population and build a bridge.

Fill gaps before they exist: Although easier said than done, as outreach and assessment procedures and partnerships are built out, it’s imperative that communities understand what options are on the table for their citizens.

Here are some possible ideas:

- Connect with local charities and nonprofits (American Red Cross, Council of Churches, JCC) to assess and map their funding, services, and programs for aging adults.

- Advocate with local landlords and property management companies for dialogue around possible evictions or rent increases so there is time to plan ahead or supplement rent.

- Explore money management offerings for seniors to help them plan spending and allocation of social security or relevant funds. Long-term budgeting may not be an immediate fix, but may provide a roadmap toward stability.

Tailored Permanent Supportive Housing Models

The promising Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) models described below, which integrate geriatric-focused care with housing, showcase how tailored PSH programs can effectively support older adults previously experiencing homelessness.

Hearth’s Permanent Supportive Housing Program: Hearth operates 228 rental units across several residences in greater Boston. The program model combines PSH with geriatrics-focused services and care, with an interdisciplinary team at each residence consisting of social workers, nurses, and resident assistants who manage and coordinate geriatrics-focused services and care, offers group activities and shared living spaces to combat social isolation, assists older adults with substance use disorders through on-site groups and counseling, and provides targeted support to individuals with mental and behavioral health issues (Brown et al., 2013).

Mission Creek Apartments: Mercy Housing’s Mission Creek Apartments in San Francisco dedicate 51 units to older adults aged 61 and above experiencing homelessness. The program employs two on-site case managers, arranges outside case management and in-home support service, and offers an adult day health program that provides nursing, food, physical therapy, and socialization services. A study found that through the prevention of nursing facility stays, PSH placements at Mission Creek saved an estimated $9.2 million in Medicaid and Medicare costs over a seven-year period (Bamberger & Dobbins, 2014).

At Home/Chez Soi: At Home/Chez Soi was a four-year project in five cities in Canada that assessed the impact of a Housing First PSH intervention for adults experiencing homelessness with mental illness. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either usual care in the community, or to the Housing First intervention that provided rent support and intensive case management or assertive community treatment based on need. The project’s results showed that both younger and older adults who participated in the Housing First PSH program experienced significant improvements in housing stability, and older adults in the PSH program experienced even greater improvements in mental health and quality of life outcomes compared to their younger counterparts (Chung et al., 2017).

CAPABLE: A pilot study by the University of Southern California is testing the effectiveness of an intervention that integrates a home-based, geriatrics-focused model of care – the Community Aging in Place–Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE) program – into PSH settings serving adults aged 50 and older. CAPABLE provides clients with visits from occupational therapists, nurses, and a handyperson over six months to enhance older adults’ independent living skills. The original CAPABLE intervention with low-income older adults demonstrated promising outcomes, such as reduced difficulty performing activities of daily living and improved quality of life (Szanton et al., 2011; Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2017). Findings from this ongoing pilot study evaluating the impact of PSH + CAPABLE on client outcomes will speak to the effectiveness of this approach for supporting older adults experiencing homelessness and identify any needed modifications.

PACE: St. Paul’s Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) in San Diego has pioneered an innovative approach to address homelessness among older adults. While PACE is a widely recognized model for delivering comprehensive medical and social services to older adults who are dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare, it does not offer housing to participants. Through strategic collaborations with housing developers, St. Paul’s PACE has bridged this gap; California-based developers provide housing, and St. Paul’s PACE delivers wraparound services to eligible seniors formerly experiencing homelessness. These partnerships have resulted in over 200 placements of formerly homeless older adults into permanent supportive housing programs with comprehensive wraparound services (St. Paul’s PACE, 2023). Since PACE centers are widely accessible throughout the country, combining PACE with local housing resources has the potential for broad replicability as a national model.

Colma Veterans Village: A multi-agency collaboration between the San Francisco VA HUD–VASH program, San Francisco VA Health Care System, Health Plan of San Mateo County, the Public Housing Authority of San Mateo County, Mercy Housing, Brilliant Corners, the Town of Colma, and the Archdiocese of San Francisco implemented this intensive PSH model to address the housing and health care needs of older veterans experiencing homelessness (Pandit & Brown, 2021). The model is part of a collaboration between VA’s Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care and HUD-VASH (Lee, 2021). The apartment building dedicates half of its 66 units to older veterans. Health care services are provided on-site by a team of VA clinicians, including primary care providers, a geriatrician, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, and HUD-VASH social workers, and there is a Resident Service Advisor on staff. An ongoing evaluation is focusing on quality improvement and comparing health care utilization between Colma Veterans Village residents and a control group of HUD-VASH sites that do not have an augmented on-site team-based model (Fabiny, Madsen, & Der).

Welcome Home: A collaborative of individuals in Chattanooga, Tennessee, created a housing community specifically focused on adults needing respite during cancer treatment or hospice care. Led by a social worker with hospice experience, the community provides a supportive environment in partnership with local agencies to address the complexity of medical needs and address the unique aspects of end of life for individuals experiencing homelessness.

Take Action

Addressing Homelessness among Older Adults in Your Continuum of Care (CoC)

Learn from those with lived expertise: Create a space and mechanism where individuals with lived experience or those currently experiencing homelessness can inform your programs and policies for this population. Listen to their stories and experiences but also bring ideas of possible solutions for their feedback. Lastly, it’s important to honor and compensate these individuals for this time.

Expand your Point-in-Time (PIT) count categories: If your CoC hasn’t already, consider expanding the core questions of your PIT Count Survey for 2024 to include a question on whether or not the individual is above the age of 55. This data could inform the severity of the issue locally and help with appeals and the design of new programming.

Expand the definition of case management: Consider exploring partnerships and cross-system education that would allow case managers to expand their expertise to include a baseline understanding of Medicare, vouchers, and other programs dedicated to senior citizens. Although many of these are complex, these mechanisms are the tools that can often supplement and support older adults.

Addressing Complex Medical Needs of Older Adults Experiencing Homelessness in Your CoC

Although the homeless response system often plays a frontline role in working with these populations, there are major opportunities ahead for health departments, health systems, and Medicaid providers to show up and support this subpopulation. Below are a few examples.

Increase access to services to match this subpopulation’s physical and behavioral needs: Many individuals experiencing homelessness report barriers to receiving routine health care, including treatment for substance use, mental health treatment, and preventative care. These barriers are extremely relevant to aging populations as well. Thus, health systems and homeless response systems must partner in the development of behavioral health offerings that are trauma-informed and accessible to all. These programs must not be limited to individuals experiencing homelessness, but also provide a pathway to care as individuals are connected to housing.

Explicitly call out resources for this subpopulation: Many resources related to health and housing are targeted at specific subpopulations like youth, pregnant women, or veterans. As programs, policies, and services are designed for aging adults, it’s imperative that all sectors make an effort to clearly outline and demarcate what’s available and important for this group to know. Health departments can add a sub-header to their website on housing. Health systems can develop one-pagers and share them with community health workers or ER staff. The more widespread and clearly outlined this information is, the better.

Increase street medicine and medical outreach teams: Although many statistics capture the prevalence of individuals over the age of 50 within shelters, unsheltered seniors and aging adults must receive access to care – and that most often requires health systems and public health entities to reach individuals where they are. Street medicine programs are routinely cited as key relationship-building and outreach services that can provide for the most vulnerable individuals and connect them to basic care. This targeted outreach can also provide an avenue for individuals to connect to housing navigation and receive assistance in navigating the barriers in returning to housing.

Build a collaborative task force with Medicare, Medicaid, and other social services: Inviting key leaders and representatives from social services in your area, particularly the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), can be transformative in both advocacy and implementation. CMS leaders have a clear understanding of state policies and programs that may be available or in the pipeline for this population, whether that be through Medicare or Medicaid demonstrations. By bringing these different viewpoints together, this task force can monitor, assess, and take actions to address this critical issue locally.