Health inequities are rooted in complex, interlocking, and seemingly intractable systems. Yet improving health and health equity at a sustainable scale requires changing those systems. How can leaders in the health care and social sectors drive significant advances toward systems change?

In 2020, Community Solutions and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed a three-year, cross-sector “Healthcare and Homelessness” pilot at five sites, with the goal to make “measurable progress toward ending homelessness, with a focus on building racially equitable systems.”

Using the “Water of Systems Change” framework from social impact nonprofit Foundation Strategy Group (FSG), the following brief lays out how the pilot’s work met the six conditions of systems change and the strategic decisions that led to its success. Other organizations and partnerships can build on this work to develop their own roadmaps to systems change.

A working definition of systems change

As outlined by Abercrombie, Harries, and Wharton, systems change is: “…an intentional process designed to alter the status quo by shifting the function or structure of an identified system with purposeful interventions. It is a journey which can require a radical change in people’s attitudes as well as in the ways people work. Systems change aims to bring about lasting change by altering underlying structures and supporting mechanisms which make the system operate in a particular way. These can include policies, routines, relationships, resources, power structures and values.”

The conditions of systems change

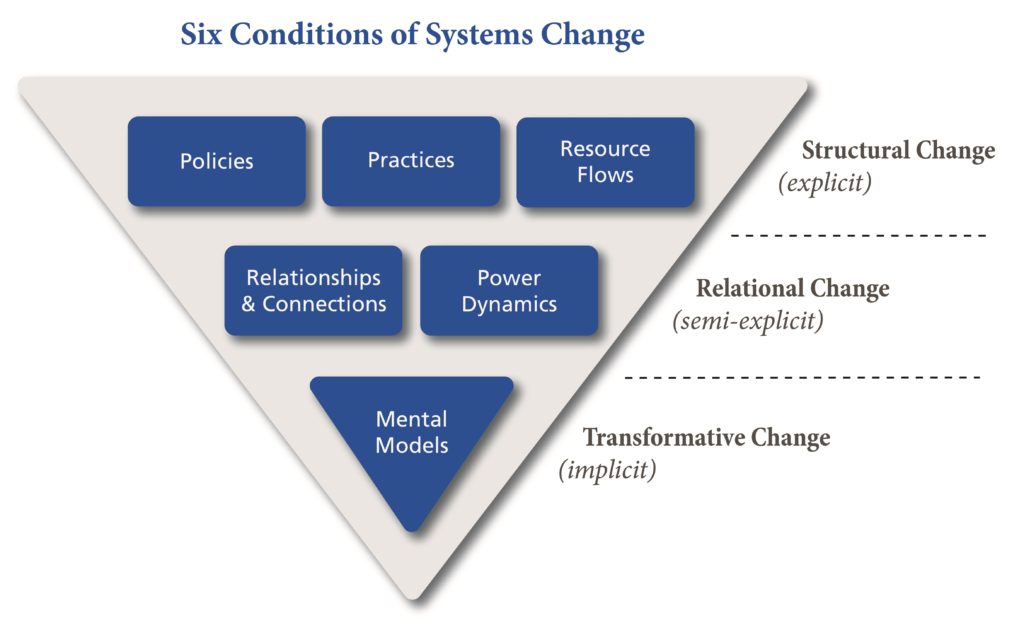

According to FSG’s model, the “water” of systems change describes the conditions surrounding complex problems, including “government policies, societal norms and goals, market forces, incentives, power imbalances, knowledge gaps, embedded social narratives, and many more.”

These conditions “impede or enable social change” at three levels, as shown in Figure 1.

- Structural change: Policies, practices, and resource flows

- Relational change: Relationships and power dynamics

- Transformative change: Mindsets or mental models

How do these conditions translate into action to effect systems change? As one of its authors notes, “it is impossible to change the system in any sustainable way without making significant progress at all three levels.”

Similarly, in “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System,” the seminal systems change thinker Donella Meadows writes, “Paradigms are the sources of systems.… You could say paradigms are harder to change than anything else about a system…. But … [a]ll it takes is a click in the mind, a falling of scales from eyes, a new way of seeing.”

The Healthcare and Homelessness Pilot

Homelessness in the United States is persistent and growing, and homelessness has been shown to drive poor health. A recent large-scale mixed methods study found that people experiencing homelessness “reported poor health and many health challenges, … poor access to health care, … high rates of acute and emergent health care utilization, … and symptoms of mental health conditions.”

The Healthcare and Homelessness pilot, described in detail in Health Affairs Forefront, developed cross-sector programs to reduce inflow, otherwise known as preventing first-time or re-entry into homelessness, and to increase outflow from homelessness.

Launched in 2020, it spanned three years at five sites: Chattanooga, Tennessee; Anchorage, Alaska; Washington County, Oregon; and Bakersfield and Sacramento, California. Each site involved local health care organizations, predominantly from three national health systems — Kaiser Permanente, Providence Health, and CommonSpirit Health — with a deep commitment to addressing social drivers of health.

Each pilot also included the local Continuum of Care (CoC), the HUD-funded group of local service providers that coordinates funding and delivery of services to people experiencing homelessness.

By building on existing structures, processes, and relationships, the pilot leveraged two conditions of systems change. First, all the CoCs in the pilot had adopted the Community Solutions’ Built for Zero methodology, meaning that they are committed to obtaining real-time by-name data on people experiencing homelessness in their community and have defined a shared goal to end homelessness for targeted groups.

Second, in some sites, health care organizations were already committed to working together at the start of the pilot. As a result, the groundwork for structural systemic changes in cross-sector processes and relationships had been laid.

The pilot sites co-created and launched cross-sector programs including data-sharing between the homeless response and health care systems, stronger processes to identify homeless patients in the emergency room and refer them to homeless response services, and joint case conferencing. In one site, four health systems each committed $1 million over three years to a funder’s collaborative to support the local homeless response and provide additional capacity. All the sites continued the work after the pilot ended in December 2023; the participating organizations were committed to ongoing collaboration and change.

Mapping the pilot to the conditions of systems change

Leveraging all the conditions of systems change in Figure 1, the pilot sites’ work was interdependent and mutually reinforcing within and across the three levels of change.

Structural change: New policies, practices, and resources

The implementation of case conferencing at four pilot sites represented a systemic step toward providing more holistic and effective care. Joint case conferencing allowed health care and housing case managers to collaborate to review the needs and current situation of people experiencing homelessness and find resources to help them.

Health care case managers could connect people experiencing homelessness with primary care or health insurance coverage, while housing case managers could help people find shelter or connect to other resources within the homeless response system.

Case conferencing, part of the Built for Zero model, was already in place in each pilot community, but workflows and documentation had to be expanded to include discussion of health-related issues and referrals to health-related resources. Health care brought resources — new case managers, or existing staff taking on a new role — to participate in the case conferences.

Data sharing, with signed agreements for data integration, was a necessary precursor to joint case conferencing. It was a significant structural change which required not only new policies, practices, and resources but also a significant mental model shift.

Concerns about privacy and security, complex regulations, differences in data structures and terms, and fears of losing control over data all created challenges and an initial conviction that data sharing could never work. Once the barrier was broken, however, it sent a signal that data sharing is possible (and legal), paving the way for other organizations to follow suit.

Relational change: Relationships, connections, and power dynamics

Relational change within and across sectors is hard work. Health care and community-based organizations operate with different, sometimes conflicting, language and cultures.

The pilot participants’ journeys across the five sites were similar — it took up to 18 months for the groups to coalesce and develop trust. Documented policies and processes (structural change) helped mitigate the impact of staff turnover when new relationships had to be formed. Working together to solve problems like how to share and integrate data strengthened the relationships.

Power dynamics evolved over time. Initially, some health care organizations expected the homeless response system to prioritize their patients — to find housing for their high-cost high utilizers and frequent emergency room patients — only to discover that the CoCs had their own, often different, methods to assess and prioritize people’s needs and housing placement.

With an eye on the pilot goals and a commitment to explore mutually beneficial solutions, and after months of discussion, the organizations at each site arrived at a mutual understanding and developed pilot goals together.

Transformative change: Mental models

Perhaps the most striking change occurred in the health care systems’ mental models — the sine qua non of systems change. Health system participants’ attitude toward the CoCs moved from “solve my problem” to “how can I help.”

Rather than see solving homelessness as the responsibility of the homeless response system, both sectors embraced joint accountability. One participant commented, “Case Conferencing in our community is going wonderfully as we now have all of the major health plans at the table. It has moved from the pilot phase to just a normal part of our operations.”

Health care system leaders widened their view of accountability beyond their patients to addressing homelessness across their community. They stated that once they saw this perspective, they couldn’t go back.

A broader view of systems change

Mutual reinforcement

Although the Water of Systems Change framework presents six distinct conditions for change, these examples demonstrate that they are intertwined and permeable. Building data-sharing agreements, for example, required a shift in mental models toward a belief that it could be done, development of relationships between the housing and health system participants (and their lawyers and data managers), and codification of the processes and workflows to share and use the data.

Replicating and scaling

The work is moving from pilots toward lasting change. Strategies to replicate and scale the new system integration initiatives are following natural systems pathways such as replication within organizations and expansion to adjacent geographic areas. For example, the data sharing agreements developed by the pilot sites may be adopted elsewhere in their regional or national health care systems. Similarly, the health system collaboration with one county’s CoC is expanding to adjacent counties, and one managed care organization’s pilot work will be extended to the rest of its service area.

A systems change roadmap

Pilot leaders’ strategic decisions demonstrated critical design principles for collaboration and systems change.

Goals and pathways to reach them: Set ambitious goals for systems change to inspire participants, but be realistic about how long it will take to achieve them.

Pilot leaders knew their goals were ambitious, but they wanted to create a compelling vision. As the pilot progressed, they revised goals and strategies to better fit the realities of sites’ needs and capabilities. The COVID-19 pandemic required mid-course adjustments but did not derail the overall goals.

System boundaries: In defining what is and is not included in a systems change initiative, balance what’s meaningful and what’s manageable.

In drawing system boundaries, the pilot sites built on existing structural conditions in the CoCs and existing relationships among the health systems. They also began with a narrow target population, people who were experiencing chronic homelessness and likely to be high utilizers of health care. The pilot included social service organizations who were already part of the CoC and focused on those whose services were most relevant to the target population. These boundaries helped manage scope and create the conditions for mutually meaningful impact.

Relationships and power dynamics: Explicitly design and model new mechanisms to share power and decision-making.

The pilot was jointly led by health care and homeless response organizations, starting with the Community Solutions and IHI leaders. This choice signaled the importance of power sharing and joint decision-making, supporting other conditions for systems change.

Levers of change: Focus on high-impact, lower effort levers grounded in local needs and capabilities.

While the pilot was launched with an overall theory of change and a menu of options for health care organizations to reduce homelessness, the pilot sites developed their own initiatives based on local goals, needs, and capacities. This more organic, locally-driven approach improved buy-in and impact.

Defining and measuring success: Link metrics to goals.

Building from their local goals, each site developed metrics of success. Just as the long term goals were to reduce homelessness and build new systems, but the pilot goals were to begin building the pathways to get there, the pilot success metrics related primarily to the strength of the cross-sector collaboration, the development and codification of new structures, the shifts in mental models, and funding commitments for the future.

Use frameworks judiciously: Frameworks are guidelines, not prescriptions.

The Water of Systems Change framework is a helpful model to identify and address known components of systems change. However, as shown above, the relationships within and among the components are fluid. This framework, like the pilot’s initial Theory of Change, is a useful starting point, but its true value is stimulating careful thought about what’s required, by whom, and by when to move toward systems change that lasts. For example, while this pilot was not explicitly organized around the Water of Systems Change framework, it implemented replicable activities in each condition that cumulatively led to systems change.

Conclusion

The Healthcare and Homelessness three-year pilot illustrated several pathways to systems change. While each site mutually established distinct local priorities and goals, all sites made progress on shifting the conditions of systems change. Their commitment to continue working together after the pilot ended suggests that a true shift — one that endures beyond an intervention — has occurred. The pilot’s strategic design choices, guiding principles, and lessons learned can help other leaders build their own roadmaps to systems change.

Author Alexandra Schweitzer is an Executive Fellow at the Harvard Business School Social Enterprise Initiative, where she writes about the drivers of success for health and social care integration for individuals, communities, and systems. She has developed, led, and evaluated social drivers of health programs in numerous health care organizations.