In Jennifer Jaeger’s meetings, they have a rule.

They don’t allow blaming a person’s characteristics as a barrier to housing. They keep their conversations focused on the real cause of homelessness: system barriers.

“So, nobody is allowed to say something like, ‘we can’t house him, because he’s drunk all the time.’ No, we’ve housed plenty of people who have had alcohol problems,” said Jaeger, Community Services Director at the City of Rockford in Illinois. “We must focus on: what is it about our community and our housing structure and our landlords and our other systems that is keeping that person on the street. How can we overcome that system barrier and house that person?”

When Jaeger’s community focused on improving their homeless response system — the system in place to serve people experiencing homelessness and connect them with the resources and support they need to exit the system — to truly serve the people experiencing homelessness, they saw success. Rockford, Illinois, has measurably ended homelessness for veteran and chronic populations; now they’re working to end homelessness for all populations.

“Housing barriers are system barriers — they’re not people barriers. No one wants to sleep out in the street,” Jaeger said.

Think of homelessness as a bellwether. It’s an indicator for how well our systems are serving the needs of populations who are often the most marginalized, oppressed, or disenfranchised.

If homelessness is the result of systems failing these individuals — the solution lies in fixing these systems so they are designed to continuously end homelessness for all populations.

This video was the product of insights and partnership with various experts who took time to review the content. We would like to extend our appreciation to James Lee of James Lee & Associates, Tyra Thomas of Street Voices of Change and John Brady of Lived Experience Advisers.

The challenge is that homeless response systems in many communities have not historically been designed to drive and sustain population-level reductions in homelessness.

Societal and structural forces make people at risk of experiencing homelessness. But systems can inadvertently keep them there. Here are some of the common challenges that keep these systems focused on responding to — instead of measurably ending — homelessness:

A lack of clear authority

There are numerous organizations tasked with addressing homelessness in a community, including: the housing authority, the Veterans Affairs office, shelters, and street outreach providers. While many agencies, organizations and people are dedicated to providing services for people experiencing homelessness, no single entity in a community is accountable for ending it..

The lack of a feedback loop as dynamic as the issue

Many U.S. communities depend on the Point-in-Time count, an annual street count of people experiencing homelessness. However, this one-time snapshot does not show a clear picture of how homelessness changes from night to night, who is entering and existing the homeless response system, and the urgent needs of the people moving throughout it.

Without a shared real-time understanding of every person experiencing homelessness by name, it’s difficult to accurately assess whether a community’s strategies are adding up to reductions in homelessness.

In order to solve homelessness, communities need to be able to answer the following questions: Are all of our programs and investments adding up to the thing we really want: reductions in homelessness over time? And if not, how quickly would we know, and how quickly could we pivot?

A lack of shared accountability for ending homelessness across upstream and adjacent systems

People experiencing homelessness — or at risk of falling into it — are touched by many other systems of care along the way, which include health care, criminal legal system, to name a few. By default, homeless response systems aren’t set up to coordinate with these upstream systems — which means. they’re not working together to prevent people from entering into homelessness.

Communities cannot reliably and sustainably end homelessness without addressing inflow — preventing people from experiencing homelessness in the first place. We recognize that reducing inflow into homelessness demands that society moves beyond managing the crisis of homelessness. It requires other sectors outside the homelessness response system to take responsibility for stabilizing people most at risk of homelessness.

“We must focus on: what is it about our community, and our housing structure, and our landlords, and our other systems that are keeping this person on the street.”

– Jennifer Jaeger, Community Services Director at the City of Rockford in Illinois

But homelessness can be solved when community-wide systems are designed for population-level reductions.

More than 80 communities in the U.S. are working with Built for Zero to understand what it takes to solve homelessness as a systems problem. And by treating homelessness as a systems problem, Built for Zero communities are seeing results: 14 communities have functionally ended homelessness for a population, and 44 communities have achieved a reduction in homelessness.

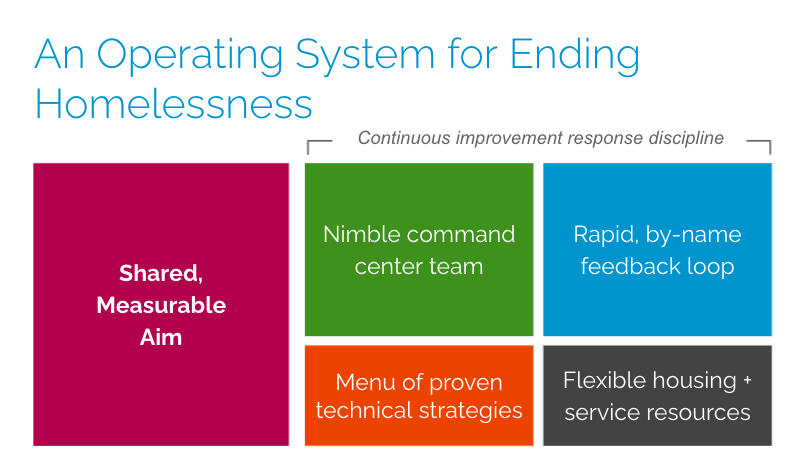

As they make progress, they have identified five key features of a community-wide systems designed for population-level reductions in homelessness:

A shared, measurable aim

The first step for communities in Built for Zero is to come together around the community-wide goal of ending homelessness. Adopting a shared definition, functional zero, helps ensure that more people are being connected to housing than are entering the homeless response system.

A nimble command center team

Everyone who touches the issue of homelessness (nonprofits, housing authorities, local government, the VA, the CoC) works together every week toward a shared definition of zero. Ad hoc teams are ready to spring up and stand down based on the key problems to solve at any given time. We are also working with communities to explore how we can develop cross-sector accountability structures that work together to reduce inflow into homelessness.

Rapid, by-name feedback loop

All agencies in a community collect and report quality, real-time, by-name data on people experiencing homelessness in a shared database. They use the data to measure whether the overall number of people experiencing homelessness is going up or down, and test different strategies and interventions to see what drives reductions.

Menu of proven technical strategies

Once a community has a clear picture of the homelessness in their community at any given time, they can convene key stakeholders in the issue to test strategies and ideas to target systems improvements.

Flexible housing + service resources

Communities leverage their data on everyone experiencing homelessness and housing availability to make targeted investments that align the needs to the existing resources in the community. They can secure the housing resources they need, and target them for the greatest possible reductions in homelessness.