Growing up in Colorado, Viviana Cervantes, 27, had encountered multiple systems of care as a youth.

She spent several years in foster care, and her family also experienced housing instability and homelessness for a time. After exiting the care system, she went directly to college, but found that transition to be a difficult one.

“I just didn’t have all the right tools to be able to be successful,” she said.

“I don’t know what I was supposed to have. I just know I didn’t have it.”

VIVIANA CERVANTES

When college classes paused for semester breaks, she explained, she would often have nowhere to go without risking a return to unsafe or unstable situations. She felt lost and ill-equipped to navigate this new stage of life after exiting the foster care system.

“I don’t know what I was supposed to have,” she said. “I just know I didn’t have it.”

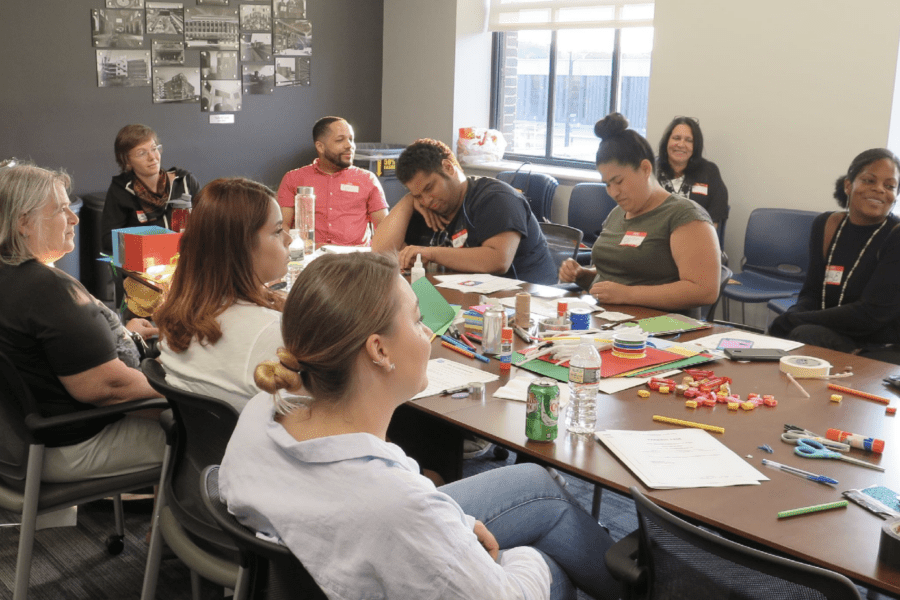

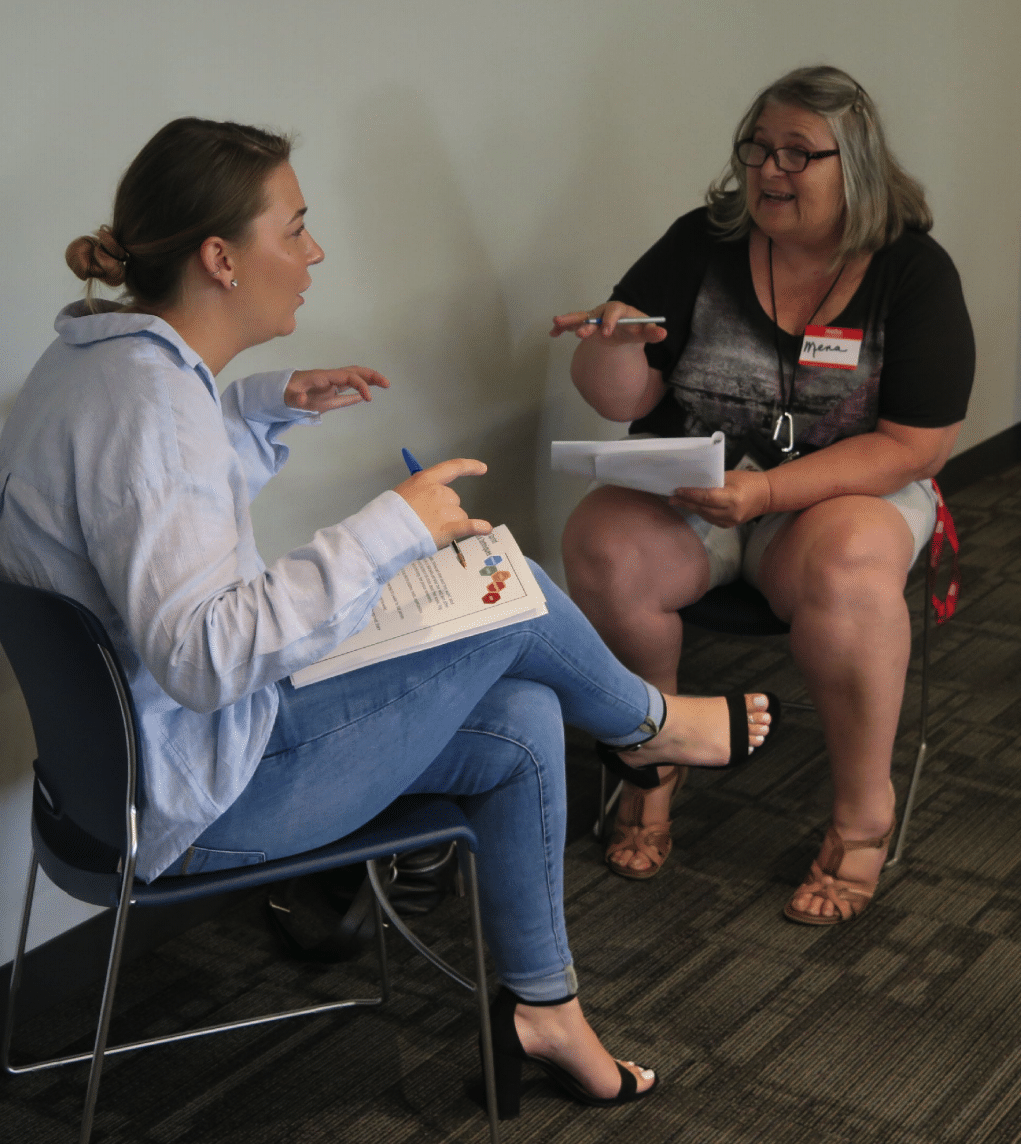

In March 2021, Cervantes was one of several youth participants in a design workshop in Denver aimed at improving experiences of youth and young adults in systems of care. Over several sessions, she was able to share her story to adult community stakeholders working directly in the systems she had traversed, including homeless response and foster care. Cervantes was eager to contribute her insight and expertise to improve the experience for other young people facing similar situations.

“When I’m able to step forward and just speak out about my experience to somebody who is in a position to be able to change something…I’m like, yep. I’m there,” Cervantes said. “It’s going to help people in the future, even if it’s not me anymore.”

Designing better systems with lived expertise

The voices of these young people are often missing from service design, delivery, and policies in systems of care they touch. This is a problem Cheryl Heller feels is solvable through her area of expertise — design. For many years now, Heller has been teaching people how to use design to help solve complex social problems.

Heller and Built for Zero communities in Denver, Phoenix, and Springfield, Massachusetts, have collaborated to host several workshops with the intent of improving systems by utilizing tenets of design, centering and serving the needs of the people who interact with these systems of care.

“People understand it’s a best practice and good for the work to bring young people in, but it’s a difficult process to engage in, and many people just don’t know how to do it.”

RAMINA DAVIDSON

A designer, author and educator, Cheryl Heller, PhD, is president of the MeasureD Lab and Chief Design Officer at Viridi Parente, Inc. Heller wants to help communities redesign their homeless response systems by bringing in a critical but often overlooked element — the insight of people with lived expertise of these systems.

Built for Zero communities commit to including people with lived experience into system design work. Gathering qualitative data about the experiences of people being served by these systems allows for intentional improvement of the timeliness of service delivery, while ensuring the dignity and respect of each individual is upheld throughout.

Heller’s focus on system design has been specifically on the experiences of youth and young adults in the many systems they may interact with, which can include juvenile justice, foster care, and homeless response systems.

“People understand it’s a best practice and good for the work to bring young people in, but it’s a difficult process to engage in, and many people just don’t know how to do it,” commented Ramina Davidson, Zero for All Strategy Lead at Built for Zero.

“What I have seen is that being able to design and being able to use the tools of design gives people a sense of agency.”

CHERYL HELLER

“Cheryl’s way of doing the work is codified in a way that makes sense,” Davidson said. “It moves forward in a way that really does start to change the system and really uses the young people as leaders in the process.”

Indeed, the workshops are not only meant to incite broader systems change, but to also provide valuable skills to the participants as well.

“What I have seen is that being able to design and being able to use the tools of design gives people a sense of agency,” Heller said. “They have a way to think about current situations and what they might want. And they have a set of tools for beginning to change things from current status to desired state.”

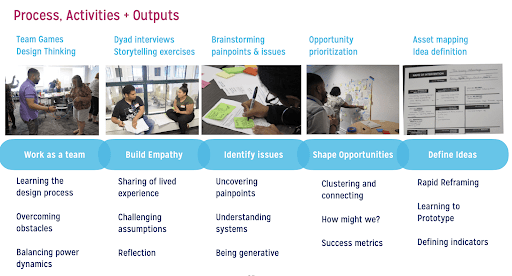

Through these design workshops, adult community stakeholders and young people gain access to the techniques, processes, and approaches that allow them to improve experiences for others currently in the systems and be part of the solutions to end youth and young adult homelessness. The intentional, collaborative design process allows the young people and adults to work as equals, understand these systems from different perspectives, and identify issues and produce plans to address them.

“I don’t think you can do the work of ending youth homelessness without bringing in your stakeholders and young people to design what you should be doing,” Davidson said. “You need to bring them in to get their perspective and their view — otherwise you only have 20% of the picture.”

Redesigning the system

In March 2021, a mix of community stakeholders from a variety of local systems of care and young adults with lived expertise gathered virtually to explore how to better shape the experiences young people have with these systems.

The “adults” were professionals working across the same community systems, including juvenile justice, nonprofits, and local and federal government agencies. The young adults participating each came with lived expertise within these systems, and in keeping with fairness best practices, were all fairly compensated for their time spent in the workshops.

“You can’t, as an adult, go up to an intimidated young person and say, tell me what’s wrong. It just doesn’t work like that,” Heller said. “You need a process that invites them in.”

To begin, youth and adults participate in exercises and games that level the playing field, in order to get everyone comfortable with both talking and listening to each other.

Cervantes appreciated the intentional, collaborative design process. She has experience advocating for foster care youth, serving as a member of Project Foster Power, a youth-led advocacy group dedicated to improving the Colorado foster care system.

“I don’t think I’ve experienced something where professionals are that open about communicating with youth or with their peers to brainstorm how to change something,” Cervantes said. “Mostly it’s…us going to the professionals and saying, this is what needs to be changed.”

“I don’t think I’ve experienced something where professionals are that open about communicating with youth or with their peers to brainstorm how to change something.”

— Viviana Cervantes, Participant from Denver Design Workshop

Drawing the invisible map

A centerpiece of the design session is when the entire group maps out the journey that a typical young person might experience throughout a specific system.

“This was just really eye-opening for people to see the whole journey and to understand the points at which young people may have to make a decision, but they don’t have the facts,” Heller noted.

In turn, adults were able to see the effects their decisions and policies had on youth. In one instance, workshop participants discovered young people and adults even had different meanings for the same words — a discrepancy that could have significant impact on the lived experience of a young person in and outside of the system.

“It was kind of fun to see the different sides of it, because at one point they asked us: what would you change?” Cervantes explained. “And the professionals definitely would change different things than we as youth would change.”

Building out “big ideas” for system improvements

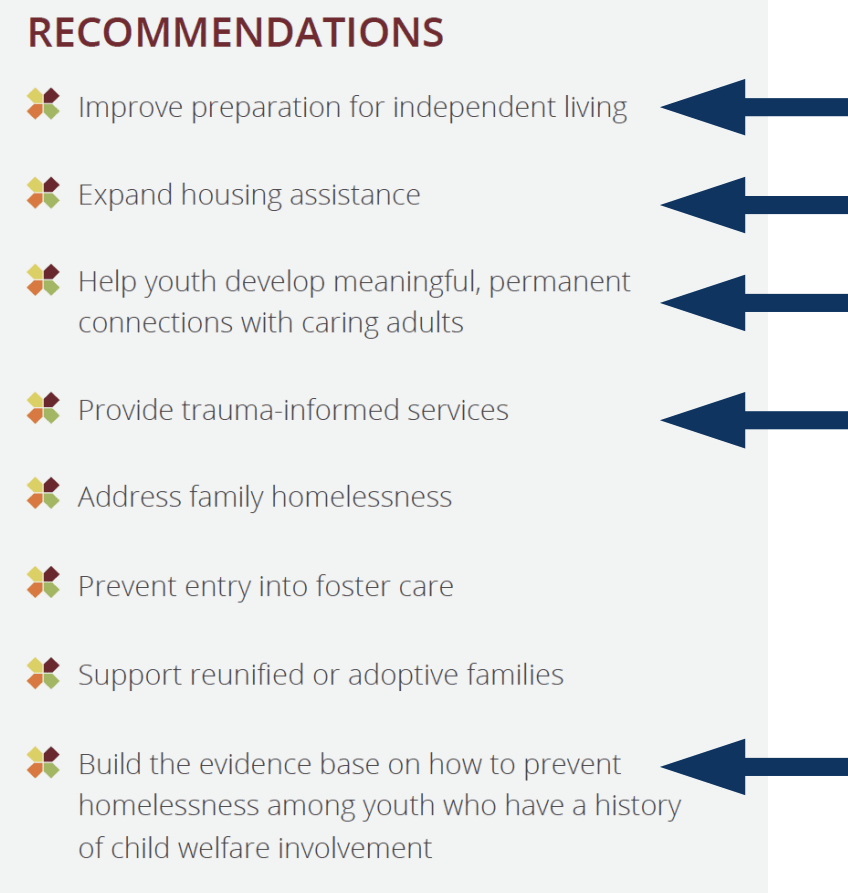

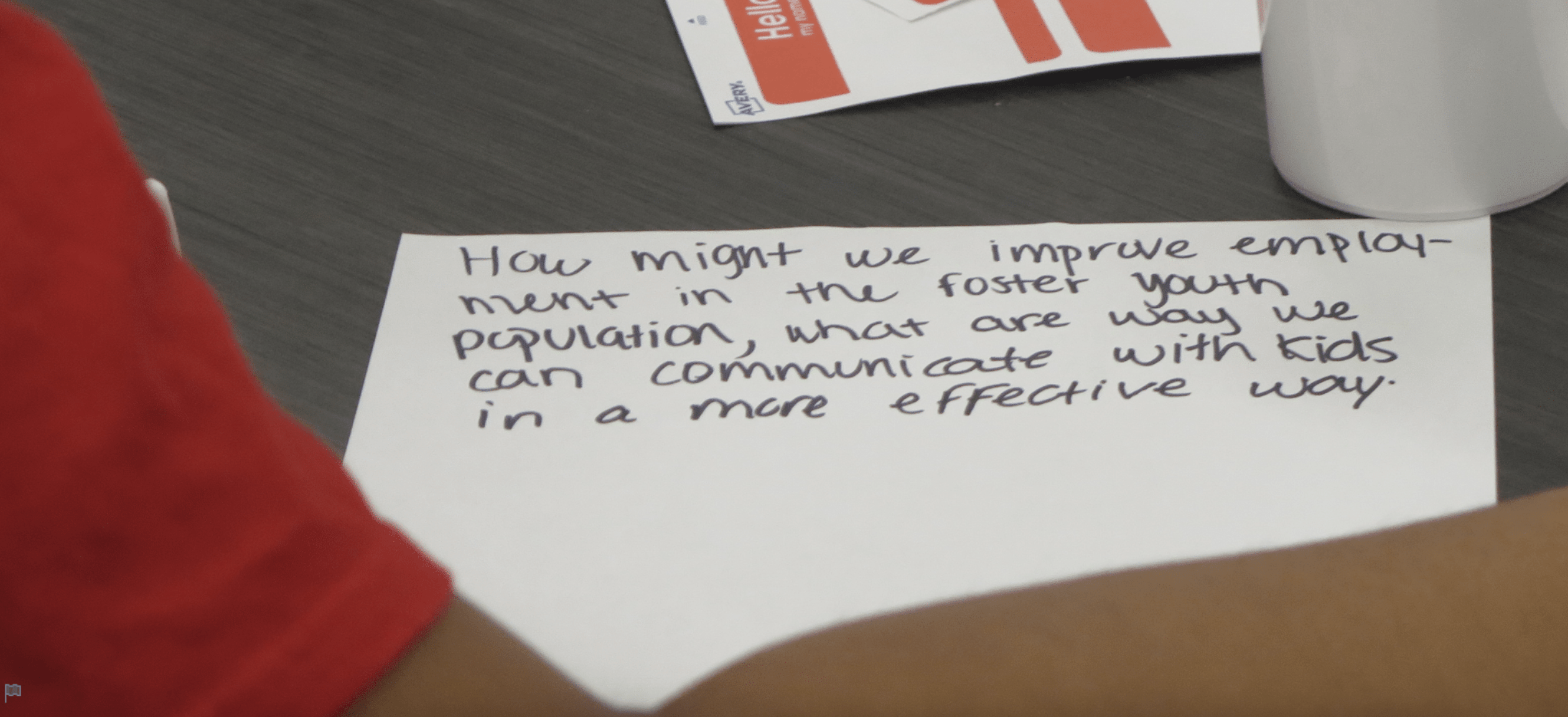

With the journey map drawn, the design group turned toward the task of identifying opportunities for system improvements, many of which came from identifying gaps in services or especially challenging experiences young people experience within the system.

One problem identified at the Denver workshop was the need to better support young people as they transition out of foster care into independent living in order to prevent potential experiences of homelessness.

A “big idea” and opportunity for improvement that emerged from the idea session was to create a network of support composed of young people with lived expertise of the foster care system for this crucial transitional time.

An opportunity for all communities

As a result of the workshop, the community stakeholders in Denver have since created three working groups aimed at tackling some of the specific issues identified to keep improving their systems.

As for Cervantes, she recently began working as a case manager at a Colorado-based nonprofit called Homeward Alliance, where she supports individuals who have experienced homelessness with contributing factors like mental health and substance abuse issues.

She sometimes can’t believe she is now one of the “adult professionals” and community stakeholders helping others within these systems. Her experience participating in the design workshop has shaped how she hopes to show up for the people she serves.

“I think if anything, I would like to be just like the professionals, and not lose sight of how my work impacts [others] and to always be willing to have that conversation,” Cervantes said.

Davidson noted that these workshops don’t have to be singular events, but can serve as launching pads for the ongoing work to include stakeholders in system improvements. Moreover, though these sessions are designed for young people, the learning from them does not have to remain with that population.

“A lot of innovative ideas come from youth and then move to other populations, in Built for Zero and elsewhere,” Davidson said.

In fact, young people interact with a variety of systems and can belong to several different populations that may experience homelessness. Youth and young adults can also be veterans, have families or be single, and can experience chronic homelessness.

“It takes many more community stakeholders than you would think to do this work across the board,” Davidson said.

“It’s a community-wide effort — it has to be when ending youth homelessness.”